Why I Say Thank You

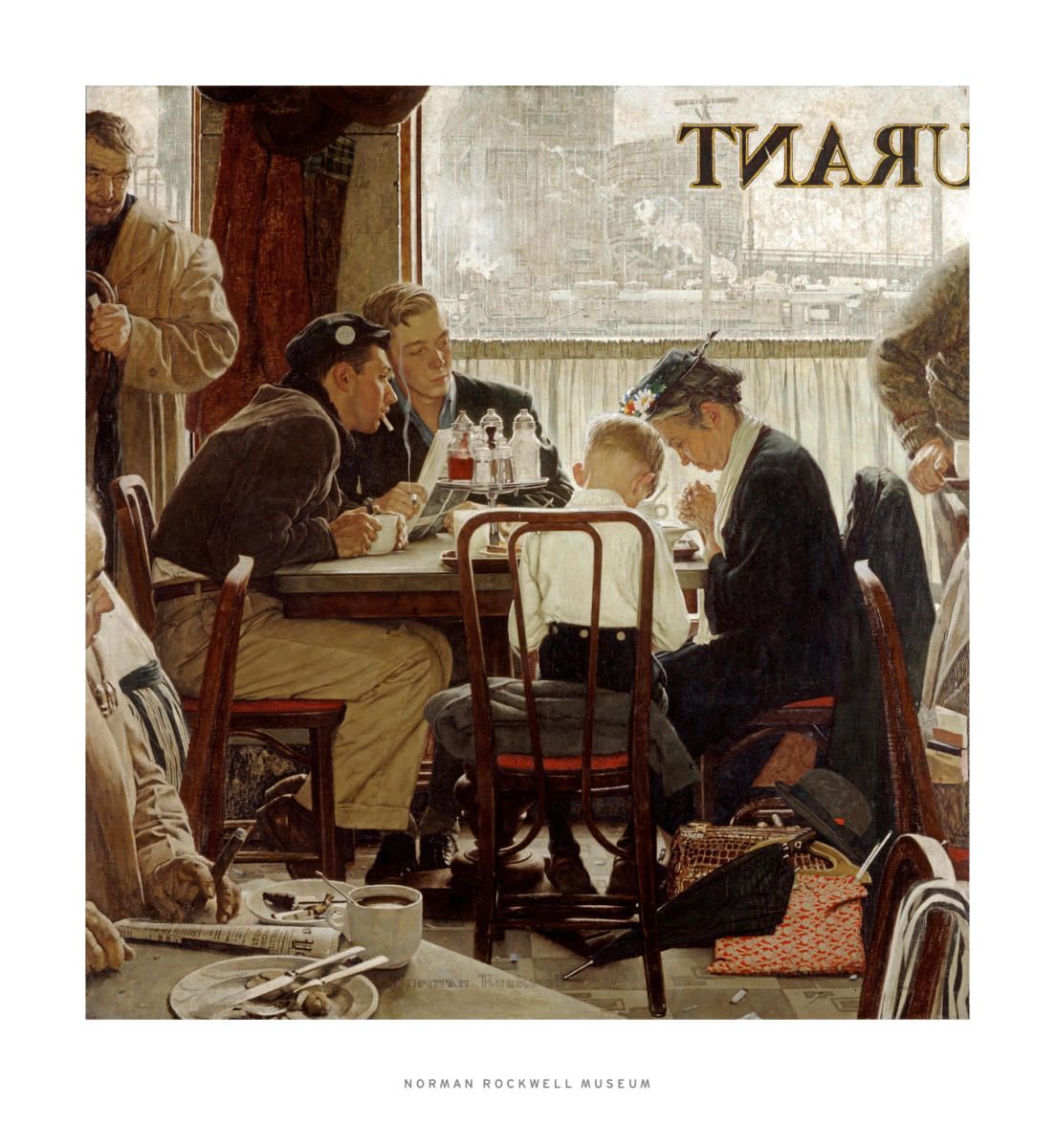

I grew up saying quick unintelligible semi-irreligious grace before dinner. We, as a young four-member family of the 1980s, said a quick, short grace that we breezed through like awaiting a green light at a street race. Grace began dinner and it wasn't said until everyone was present. It was the order before the chaos.

It was a streamlined version of the lengthier prayers my grandparents said at family gatherings and we were honoring that sentiment, to thank the powers that brought our dinners together. This daily Thanksgiving intended to say "Thanks to God for good food". Then by the age, I left home, it had become a more agnostic, somewhat secular humanistic gratitude, "Thank the universe for good food."

Years later, if I am sitting before a meal, even a burger and fries, I satisfy both God and my universe just by saying a quick, seconds-long grace. Somehow it felt arrogant to believe I deserved the food independently of anything I'd done. Without giving thanks, it seemed like I took it for granted. I could not make this myself from scratch...

Yet around me swirled a world where hard-working people went hungry, good people were starved to death by bad people, and famines diminished the human spirit and left meal tables vacant of food. There were those in my neighborhood who went hungry at night. Some people ate half a meal and threw the rest in the garbage, and some kids resented the food on their plates. Brussel sprouts, cauliflower, and water chestnuts notwithstanding... (maybe God invented some foods just to look at?)

"This food is the gift of the whole universe – the earth, the sky, and much hard work. May we live in a way that makes us worthy to receive it. May we transform our unskillful states of mind, especially our greed? May we take only foods that nourish and prevent illness? We accept this food so that we may realize the path of our practice." – Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh

When I worked abroad - first teaching in Russia, I always sought ingredients for a meal I dubbed, ‘the Russian sub’. In 2000, the Kursk nuclear submarine had just died on the bottom of the seafloor, killing all 118 of the crew. My sub sandwich had a terrible secret, its name. But somehow it stuck. My "Kursk" submarine consisted solely of the best bread, the best meat, and the best cheese wherever it was available, no matter how far afield. And whether it be a Russian kiosk, a Chinese shopping mall, or the Middle East open-air market, I would always go the distance to find something similar that would sustain me over many months. I've never been good at trying new foods, but I've always been a good traveler, and this limited-ingredient food was my enabler.

Let me tell you that the adventure lies in testing dozens of applicants to the warfare of dinner. With my broken Russian, I had to test lard, butter, and cottage cheeses; none met the prerequisites of being the best, so I modified them. Meat may have been dog or cat or _____. However, bread is a pretty solid choice, and each country has its variant, and there's a cultural variety of what they dipped or spread onto it. Bread, like no other consumable commodity, was available everywhere. Even in Russia, where the local bread is called lavash, aligned with traditions, I'd wait in the breadline to greet my 'xlyeb (bread lady)' and take four of her baguette-inspired loaves. Or in China where it may be salted, glazed, or mixed with raisins, dog or cat, it took numerous trials to find the adequate hull, the chassis, for my Submarine Sandwich.

That was it, I built the Kursk Sub and then stuck it into an oven or microwave, and I was set for dinner I could (and indeed did) enjoy without having leftover borscht, murky pâte, or sturgeon eggs on my plate. And each time I set about to eat, I quickly said grace. I wasn't one to spare minutes and bring biblical chapters and verses into it, I merely wanted to conveniently shout out to the forces that assembled my meal.

I’ve always said that I could live next to a 7-11 store or a Russian kiosk and shop for my food and instant coffee, convinced I needed little to live on in times when little was all there was to buy. I would say being able to live next to a convenience store was a ‘survival skill.’ What will you do if you can't start your morning with your "double-soy, non-fat, caramel, decaf" and you're faced with coffee, cream, and sugar? Finding some edible food was also worth giving thanks for being there when I needed it. Today's meals made from scratch aren't truly made from the field and the farm; you start midway through the process. I'm just able to begin my meal at its latest stage, pre-cooked, prepared, packaged, and ready to reheat.

The food is Brahma (creative energy). Its essence is Vishnu (preservative energy). The eater is shiva (destructive energy). No sickness due to food can come to one who eats with this knowledge.

– Sanskrit blessing

The term ‘grace’ comes from the Ecclesiastical Latin phrase gratiarum actio, "act of thanks." Britannica describes saying grace as theology, the spontaneous, unmerited gift of the divine favor in the salvation of sinners, and the divine influence operating in individuals for their regeneration and sanctification. The term appears ubiquitously.

The upshot of this is, that I always felt the need to give thanks to a God of the universe for a particular reason: I am missing some key skills when it comes to gathering the ingredients for dinner. I do not have the land for the grain for my burger bun. And I wouldn’t know what to do if I had 1000sq ft of wheat. I may be able to grow the cucumbers for the pickle, tomatoes for ketchup, the potatoes for fries, the onions, and the lettuce but I doubt they’d be ripe and ready at this single dinnertime appearance. It's a lot of trouble, especially if you live next door to a deli.

Further, I have no real skills with slaughtering cattle, although I did almost go on a true cowboy ‘ride’ in Wyoming for six weeks to deliver a herd of cattle to Denver. I instead chose a job pumping gas and checking oil which was closer to processed food, Happy Hour, and restaurants with BBQ pits. So if I had to slaughter a single cow for dinner, the rest would rot, and I'm sure a slide toward veganism would follow. I'm not a conscientious hunter-gatherer.

In this plate of food, I see the entire universe supporting my existence.

– Zen blessing

Most of us in the Western world who eat three meals a day are incompetent hunters and gatherers. And so my momentary pause to mutter the words of grace are my recognition of the farmer, the butcher, the baker, and the chain supply that brought it all together. Unlike the minute's silence for our fallen heroes on Remembrance Day, where my mind wanders off from the battlefield to any number of things that don't have to do with war, saying grace is an activity that drones in on the specific action at hand, and it's over nearly as soon as it was started.

Back to my meal before me, in this case, a burger and fries, now whether my girlfriend did all the integral cuisine calculus involved or if it was from a McDonald’s drive-thru. However, the complicated logistics of my meal came to me. It is a miracle I could not have done for myself. I know that I could not grow a cheeseburger in the rain. The universe conspired to put it all together on a plate or in a bag for me.

As long as what lay before me to consume is something I could not do on my own, so long as a whole list of ingredients comes together at an appointed time, I will thank the universe for its allowance for me to eat at a time that coincides with my hunger. I get to interrupt the heavens with words many in this world do not have the opportunity to say, and we call those words grace. Thank God there was food when I was hungry...

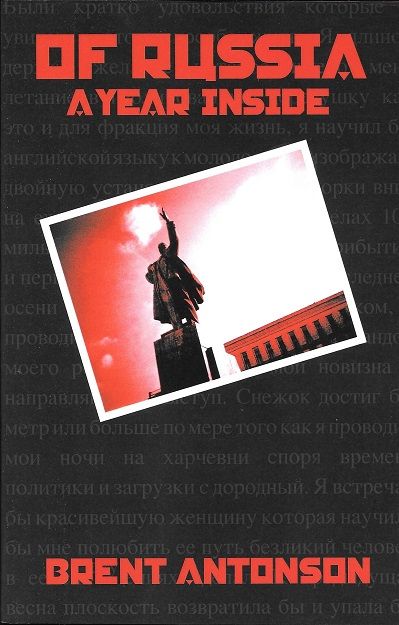

OF RUSSIA: A Year Inside

Brent (Brant is the Russian version) Antonson has seen a Russia few foreigners have. Indeed, few Russians. This young Canadian ventured to Voronezh, eleven hours south of Moscow by train, to spend a year inside a country torn by strife, fresh into a new century, and struggling with the clash between history and future. Tasked with teaching English to students at one university, and then a second, his story is riddled with romance and deception and punctuated with near disaster and disappointment. Antonson's candor and insights set Russia on the edge of failure and achievement – much like the students, he educated, filled with a dash of hope and a lump of fear. His wit did as much to get him in trouble as it did to keep him out of it.