The Complete Heretic’s Guide to Christmas

In the beginning

Let’s talk about the story of Christmas—ah, Christmas! It’s a special time of year; a time for family and friends, good tidings of great joy, and a message of peace, and love and goodwill towards all.

But apparently, for nearly as long as there has been such a thing as Christmas, Christians have been complaining that we’ve all forgotten the True Meaning of Christmas™.

So, what’s the real meaning of Christmas?

Well, to get at that, we have to go back—and I don’t just mean a mere 2,000 years. No, we have to go a lot further than that. Because the real meaning of Christmas isn’t just about presents or even the birth of a saviour. It’s a story of the sun and the moon, monsters, witches and ghosts, gods and goddesses, death... and rebirth.

I probably don’t have to tell you this, but it still often comes as a shock to many Christians that to talk about Christmas, we have to start by talking about the winter solstice.

Winter Solstice: The Reason for the Season

Since at least as far back as the late Stone Age, ancient cultures all around the world were deeply in tune with the rhythm of the seasons. They had to be: it controlled when to plant your crops when to harvest them, the mating and calving seasons of their herds, and how much food they needed to get them from harvest to harvest. Most important to them was the winter solstice.

Winter was a deadly time; people had no guarantee they would survive until spring. The winter months had plenty of opportunities to kill you; death by starvation, sickness and the cold were all too common. Daylight dwindled, darkness gathered, the land grew cold and barren, and the world languished under ice and snow. Those who kept watch on the sky feared that the days might never stop getting shorter. Maybe this would be the year that the sun wouldn’t return, and the world would end in darkness and frost. It was all in the hands of the gods.

But the coming of the midwinter Sun marked the turning point. That’s when they knew that warmth and light would come back after all. It was a time to slaughter most of the cattle so they wouldn’t have to be fed during the winter, making it one of the few times of the year when a surplus of fresh meat was available. What’s more, most of the wine and beer made during the year was finally fermented and ready to drink. And the year’s gruelling farm chores were at their lightest, giving people the free time to celebrate.

And people did.

Christmas Before Christmas

All over the world, we find that this was a time of celebration and worship. The winter solstice was the centerpoint of the ten-day Babylonian Festival of Zagmuk, celebrating the sun god Marduk's battle over darkness. The festival was celebrated with parades both on land and in rivers. Masters and slaves changed places, a mock king was crowned and masquerades clogged the streets.

Khoram Ruz

In ancient Persia, the Zoroastrians celebrated Khoram Ruz (or Khore Ruz), the day of the sun marking the victory of the Sun over the darkness at the Solstice.

Lenæa

In the Aegean world, the ancient Greek midwinter festival of Lenæa mourned the death and celebrated the rebirth of Dionysus. His priests would perform miracles on his behalf, like changing water into wine.

Brumalia

The ancient Romans celebrated the god Bacchus with drinking and merry-making, in a festival that culminated on the night of December 24th.

Saturnalia

Brumalia later became Saturnalia, a year-end blowout of food, sex and booze, including customs like the exchange of presents. The Romans also decorated their homes and public spaces with boughs of evergreen fir branches, just as the ancient Egyptians decorated their homes with evergreen palm fronds during the winter solstice.

Meán Geimhridh (Celtic Midwinter)

For the ancient Celtic Druids, the calendar revolved around solstices and equinoxes. Before them, neolithic pre-Celtic sites like Stonehenge in Britain and Newgrange in Ireland were aligned to the winter solstice sunrise, when a shaft of light would illuminate the inner chamber. Incidentally, mistletoe was also sacred to the Druids.

Byrddydd Gaeaf

In ancient Welsh mythology, the winter solstice was when Rhiannon gave birth to her sacred son, Pryderi.

Yule

The ancient Germanic tribe's winter Yule festival became so completely absorbed into Christmas that most folks don’t realize they weren’t always the same thing. From Yuletide Christmas got traditions like the Yule log, of course, but also the Yule goat, Yule boar, Yule singing, Yule candles and others, like venerating an evergreen tree.

And the list goes on. In China, Japan, Incan Peru, in the Americas and still other parts of the world, virtually every ancient culture had festivals to mark the Winter Solstice.

But of course, the Christian Christmas has absolutely nothing to do with any of that. It’s based entirely on just one thing: the story of Jesus’ birth.

The First Christmas Story

Or, actually: The First (Two) Christmas Stor(ies). Both the Gospels of Matthew and Luke give us the Christmas story. However... they aren’t the same story…

Matthew’s Story

Joseph, a descendant of David, has not yet slept with his betrothed wife Mary - and yet she is pregnant. Not willing to publicly embarrass Mary, he plans to quietly divorce her. While he is thinking these things, an unnamed angel appears to Joseph in a dream and tells him not to be afraid of taking her as his wife, because she has been impregnated by the Holy Spirit, and will give birth to a son, who they are to name Jesus. (Strangely, this is said to fulfill the prophecy that says “They shall call his name Immanuel”) Joseph awakens and does as the angel says, taking Mary home with him as his wife, but the story’s author is quick to add that Joseph does not have sex with her until her son is born. (1:18-25)

Jesus is born in Bethlehem, Judea during Herod’s reign. Incidentally, those are the only details of the nativity story that Matthew gives us (2:1).

Sometime after Jesus is born (We’re not told how much later, but from the context in verses 2:16 it’s clear this is at least a year or more later) Zoroastrian astrologers from Persia (“Wise men from the east”) come to Jerusalem, asking where the newborn King of the Jews is, since they have seen his star in the East and have come to worship him.

When the current King of the Jews Herod hears this, he is troubled, along with all of Jerusalem (2:3). He gathers all the chief priests and scribes together and demands to know where this Christ should be born. Citing the Old Testament prophet Micah (5:2), they tell him it is written that he will appear in Bethlehem. Herod secretly meets with the Wise Men to find out when the star appeared and sends them to Bethlehem, telling them to go find the young child and send word — so that he can come and worship him too... (2:1-8).

The Wise Men depart and the star which they saw in the East miraculously reappears and goes before them until it comes to a stop exactly over Jesus’ house. Rejoicing greatly, they come into the house and find the young child with his mother, and fall down and worship him. They present him with regal gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. But then they are warned by an angel in a dream that they should not return to Herod, so they head back home to Persia by another route (2:9-12).

When the Wise men leave, another angel appears to Joseph in another dream, telling him to take the family and flee into Egypt and stay there until further notice, because Herod is after them. They immediately leave by night for Egypt —just in the nick of time, because when he realizes the wise men aren’t coming back, Herod is furious and sends his troops throughout Bethlehem and its environs to kill all the baby boys two years old and under (2:13-18).

After Herod’s death in 4 BCE, another angelic dream appearance informs Joseph in Egypt that it is safe to come home to Bethlehem. But when Joseph hears that Herod’s son Archelaus is now on the throne, he is frightened to return to Judea. But after yet another angel appears to him in yet another dream to clear things up, he takes the family up into the Galilee instead and makes a city called Nazareth their new home (2:19-23). Apparently, the angel didn’t know that at this time, the Galilee was under the control of one of Herod’s other sons. (3:10). - the end (of Matthew’s nativity story) -

Luke’s Story:

One day, the angel Gabriel appears in Nazareth to Mary, a virgin espoused to a man named Joseph. He tells her that even though she is a virgin, she will bear a son named Jesus and that “He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Highest: and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David. And he shall reign over the house of Jacob forever; and of his kingdom, there shall be no end.”

He also informs her that her older, formerly barren cousin Elizabeth is six months pregnant (1:26-38). Mary quickly leaves for the hill country, into “a city of Judah” where her cousin Elizabeth lives (1:39). At this, baby John the Baptist leaps in her womb, and Elizabeth is filled with the Holy Spirit. Mary stays with her for about three months and returns to her own house (1:56). Elizabeth gives birth to John the Baptist (1:57-80).

Meanwhile, in Rome, Caesar Augustus decrees a tax “of the whole world.” Luke tells us (2:1-2) this happens when Quirinius is governor of Syria (that is, around the year 6 or 7 CE) So Joseph leaves his house in Nazareth and goes to his family’s ancestral home, Bethlehem to be taxed, taking along his very pregnant wife Mary (2: 3-5). Because there was no room for them in the local inn, Mary gives birth in the stables and lays him in a manger.

An angel, along with a multitude of the heavenly host, appears to shepherds in the countryside and announces the birth of a saviour, Christ the Lord. The shepherds go and find Mary and Joseph and the baby lying in a manger. They start telling everyone what the angel told them, making it widely known to the marvelling populace, and Mary ponders these things in her heart (2:6-19).

Eight days later the baby is circumcised and is named Jesus (2:21). After Mary’s ritual 40-day purification period ends (2:22), Joseph and Mary bring Jesus to Jerusalem to offer the traditional blood sacrifice of a pair of turtledoves in the Temple. There, a devout holy man, Simeon, blesses Jesus, saying he can die happy now that he has seen the Lord's Christ. Joseph and Mary marvel at this (despite all the advance notice given to them by the Archangel Gabriel and multitudes of

the heavenly host). Anna, an elderly widow and prophetess, also gives thanks and begins telling everyone about Jesus.

Mary, Joseph and Jesus return home to Nazareth. (2:21-39). Young Jesus grows up in Nazareth, strong in spirit, filled with wisdom and the grace of God. Every year his parents go to Jerusalem for Passover (2:40-41), where later, twelve-year-old boy Jesus will astound the teachers in the temple courts with his understanding (2:41-51).

And so Jesus grew up “in wisdom and stature, and in favour with God and man” (2:52).

- the end (of Luke’s nativity story) -

A Quick Recap:

The sharper-eyed readers among you may have noticed there are a few discrepancies between our two gospel accounts of Jesus’ birth and early years — both written by originally anonymous, admitted non-eyewitnesses, some generations after the fact (possibly in the very late first century, or more probably, the early to mid-second century).

As you can see, Matthew’s story reads like a suspenseful chase thriller: the real action doesn’t even begin until at least a year after Jesus is born. Amazingly, Matthew doesn’t even spend an entire sentence on the actual birth of Jesus, in fact, just five words tucked in one line: “…Jesus was born in Bethlehem…” Then the story goes into high gear with lots of dark happenings: Mysterious wise men from the East, a moving star, intrigue, an evil King’s plot, a late-night escape into Egypt, a horrific massacre, the holy family sneaking from place to place, on the run.

Oh, and angels appearing in dreams. Lots of angels, appearing in lots of dreams. Matthew seems to have a great deal of firsthand knowledge of what was going on in peoples’ dreams — either that, or he has a very limited imagination when it comes to plot devices.

By contrast, Luke’s story is all sunshine and light and full of cheerful details about Jesus’ wonderful birth and childhood. It’s really two stories, as he intermingles the nativity story of John the Baptist with the nativity story of Jesus, but both are angst-free tales filled with good things happening to happy people.

In Matthew anonymous angels repeatedly appear by night in dreams to the menfolk, Joseph mostly. In Luke’s version, however, the angel Gabriel shows up in waking life to the women, one appearance to each. Unlike Matthew, who puts Jesus immediately on the run to Egypt to save his life, in Luke, everyone is instantly delighted with the Savior’s birth, including the prophets who publicly acclaim him before everyone in the Temple. And while Matthew has Joseph finally arrive in Nazareth for the first time only at the very end of the story, in Luke, Mary and Joseph not only both start out in Nazareth, but they go back and forth from Nazareth to Jerusalem for Passover every year — including the entire time Matthew has them hiding out in Egypt.

Yet in spite of all these problems (and there are still so many more problems we don’t have time to get into here[1]), Christians have managed to ignore the incompatibilities and mash up the two contradictory stories into one. And so, our familiar Christmas story was born.

Yet despite these accounts in the Gospels (or at least, two of them[2]), there was still no celebration of Christmas — nor would there be for another 200 years or so...

Christmas becomes Christian

Why no Christmas? Well, for one reason, for the first few centuries of Christianity, Christians didn’t celebrate birthdays; that was what heathens did. Being born into this sinful world was nothing to celebrate; what mattered was leaving it! So instead, they celebrated feast days of saints on the date of their glorious deaths. The 3rd-century church father Origen declared it was a sin to even think about celebrating Jesus’ birthday as if he was some pharaoh. It wasn’t until the fourth century that Christians began seriously pushing for a birthday for their god, too. The problem was, when was Jesus born?

Neither Matthew nor Luke tell us when Jesus’s birthday was. So various groups of early Christians wound up celebrating his nativity on a variety of dates. The Eastern Orthodox churches said it was January 6th, a day that the Western Church observes as Epiphany, which celebrates the visit of the magi (or his baptism, or his water-to-wine miracle at the wedding at Cana, or any number of his childhood exploits, and/or all of the above and more, depending on where and when you ask). The Armenian church still maintains January 6th as the real date of Jesus’ birth.

Still, other guesses were:

• February 2nd (that’s right, Groundhog Day!)

• March 25 (now the traditional date of Jesus’ conception)

• April 19th

• May 20th, and

• November 17th

But Dec. 25th was a strong early favourite, and in the year 350, after commissioning an official study to determine the date of Jesus’ birth, Pope Julius I announced that, by amazing coincidence, it was: Dec. 25th — yes, the date of the Winter Solstice, and incidentally also the birthday a number of pagan sun gods and divine sons of gods, like Dies Natalis Solis Invicti (“the Birthday of the Unconquered Sun”).

What’s Jesus’ real birthday?

Seriously, though, what day was Jesus really born? Our only clue is that the shepherds were in the fields, watching over their flocks by night, which would only be sometime during the spring, presumably.

And is that “fact” even true?

What year was Jesus born?

You may be tempted to say the year zero, of course; which is actually incorrect — mainly because there is no such thing as the year zero. But lining up Jesus’ birthday with Year One on our calendar was a mere result of bad guesswork, and today no one thinks the first year of our Lord is the actual year of our Lord’s birth. And really, we don’t know for sure what year the correct year may have been since the gospels disagree irreconcilably: Matthew says it was during the reign of Herod the Great (who died around 4 B.C.). Luke says it when Quirinius was governor of Syria (6/7 A.D.). a gap of at least ten years.

Incidentally, because of the conflicting information given in the gospels, we have no secure date or year for Jesus’ death, either — or indeed, for any single event in his life at all.

Where was Jesus born?

By the way, where was Jesus really born? Was it:

• In his parent’s house in Bethlehem?

• In his parent’s house in Nazareth?

• In a manger in Bethlehem?

• A cave in Bethlehem housing a manger? (a cave that also once happened to be a local pagan shrine to Adonis; according to St. Jerome)

• Somewhere else altogether, such as Cana or Capernaum in the Galilee?

All these guesses have been put forward at one time or another, but again, we can’t be certain. The Gospels not only contradict one another, but don’t appear particularly trustworthy as biographical data in the first place — so much so that a growing number of secular scholars argue that Jesus never existed at all.[3]

The Evolution of Christmas

Despite all these gospel plot holes, discrepancies, outright contradictions and uncertainties, over time they all became more or less successfully swept under the rug. By the late 3rd century, the celebration of Christmas was off and running strong: first as an established church holiday, then an official Roman holiday, then a full-blown twelve-day holy festival. It was also a popular date for the coronation of new kings. But Christmas wasn’t through evolving; not by a long shot. And while Christianity seemed to have conquered all its old rival religions, in truth, the pagan world still had plenty of traditions, superstitions and gods that people clung to. So they shaved off the serial numbers and called them Christian.

For example, we don’t know when the first pagan harvest festivals were, but we know exactly when the first Christian Thanksgiving was: not at Plymouth Rock in 1621, but over a millennium before. In the year 601, Pope Gregory I gave up trying to stop the Angles and Saxons in Britain from their tradition of sacrificing oxenin late autumn. Instead, he proclaimed the first Thanksgiving — that way, at least, they would now be observing a Christian rite and not worshipping demons. Like Halloween trick-or-treating, door-to-door begging was another Pre-Christian custom that survived as the assailing tradition, where revellers went from house to house singing and demanding fruit or strong drink.

Pagan gods and goddesses found a new career as miracle-working Christian saints. Take, for instance, Saint Nicholas, a.k.a. St. Nikólaos of Myra (or of Bari), ostensibly[4] a late 3rd/early4th-century bishop from Asia Minor and patron saint of children. In his best-known legend, he secretly paid the dowries of three young girls, by dropping bags of gold down a chimney, or in a stocking that had been hung by the mantelpiece to dry. Saint Nick became a spectacularly popular saint all over Europe and Russia.

Besides being the patron saint of children, he went on to become the patron saint of a surprising number of wildly diverse other things, inc. archers, pawnbrokers (the iconic three golden balls symbol of pawnshops comes from the bags of gold in St. Nicholas’ dowery legend), merchants, brewers, sailors, pirates, repentant

thieves, prostitutes, unmarried people, students, arctic peoples like the Samoyeds of Siberia and the arctic reindeer-loving Laplanders, and still more. He also started going by a wide variety of names and featured in a wide variety of different traditions. And he seemed to acquire more miraculous abilities, and take on aspects that were strangely familiar — if you were old enough to remember the old gods like Odin from the pre-Christian days.

And speaking of the lingering old ways and the old gods, it wasn’t all just happy pagan traditions that were becoming part of the Christmas season...

Scary Christmas!

Not just Christmas, but all four of our major winter holidays — Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Eve were shaped by pagan traditions. Ghosts, goblins, witches and spirits were part of Yuletide and the Celtic Winter. It became traditional to leave out offerings of food for whatever supernatural visitor might come bumping in the night.

One such was a Hag who went by various names such as Berchta or Holda. She visited homes and judged them, bestowing blessings or curses. To appease her, folk left gifts of fish and dumplings, and oats for her horse, and everyone had to be in bed and asleep before she arrived. In Italy, Berchta became the Christmas witch, La Befana, who left presents for good children, and coal for bad ones — and if they were very bad, she might carry them down to the underworld, where her Ogre husband ate bad children.

In parts of Europe, St. Nick had a scary sidekick. In the Netherlands, he was joined by a black-skinned Moorish companion called Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) who beat bad children with switches. In German-speaking countries, the sidekick was Knecht Ruprecht (which translates as Farmhand Rupert or Servant Rupert), a stern, gloomy figure with a long beard, wearing fur or covered in pea-straw, sometimes carrying a long staff and a bag of ashes, which he uses to beat children who don’t know how to pray. Incidentally, Ruprecht was a common name for the Devil in Germany.

In Scandinavia, “Julebukkers” would go from house to house, disguised in a goatskin and carrying a goat head representing the Julebukk, the Yule Goat, originally sacred to Thor. Julebukking could feel a lot closer to Halloween than Christmas; sometimes their disguises were very frightening, and part of the tradition often included kidnapping one person from the household to join them in their revels.[5]

But the scariest Anti-Claus has to be Krampus, the Devil of Christmas. In the Alpine countries, Hungary, Slovenia and Croatia, Krampus appears in many variations. He is usually hairy, usually brown or black, with cloven hooves, goat horns and a long, pointed tongue. Sometimes he has a washtub strapped to his back or carries a sack to cart off evil children for drowning, eating or transport to Hell. The night before the Feast of St. Nicholas is Krampusnacht, “Krampus Night,” when he appears on the streets to visit homes and businesses; sometimes accompanied by female spirits called Perchten — from the word Berchta.

An important safety tip: If you encounter a Krampus, it’s customary to offer it schnapps.

Needless to say, Krampus freaks people out. The Inquisition and the Nazis both tried to stamp out Krampus celebrations and failed, so you know he’s one tough S.O.B., though even today there’s debate on whether Krampus is appropriate for children. But there are even scarier things about Christmas... I’m talking, of course, about:

The War on Christmas

Did you hear? Christmas is (once again) under attack. It’s a war — that’s right: A WAR ON CHRISTMAS! Our Christian Founding Fathers would be rolling in their graves if they knew, but thankfully there are Patriotic Christmas-American heroes, mostly on Fox News, who are willing to take a bold stand against those enemies of Jesus who would rather say “Happy Holidays!” than “Merry Christmas!” or, even worse, refer to our saviour’s birthday as “X-Mas.”

Who started this terrible war on Christmas? Was it the atheists? The Jews? Gays, Lesbians and the Transgendered? The ACLU? Al-Qaida or ISIS? The Secular Humanists? Worse! It was...

Our Christian Founding Fathers!

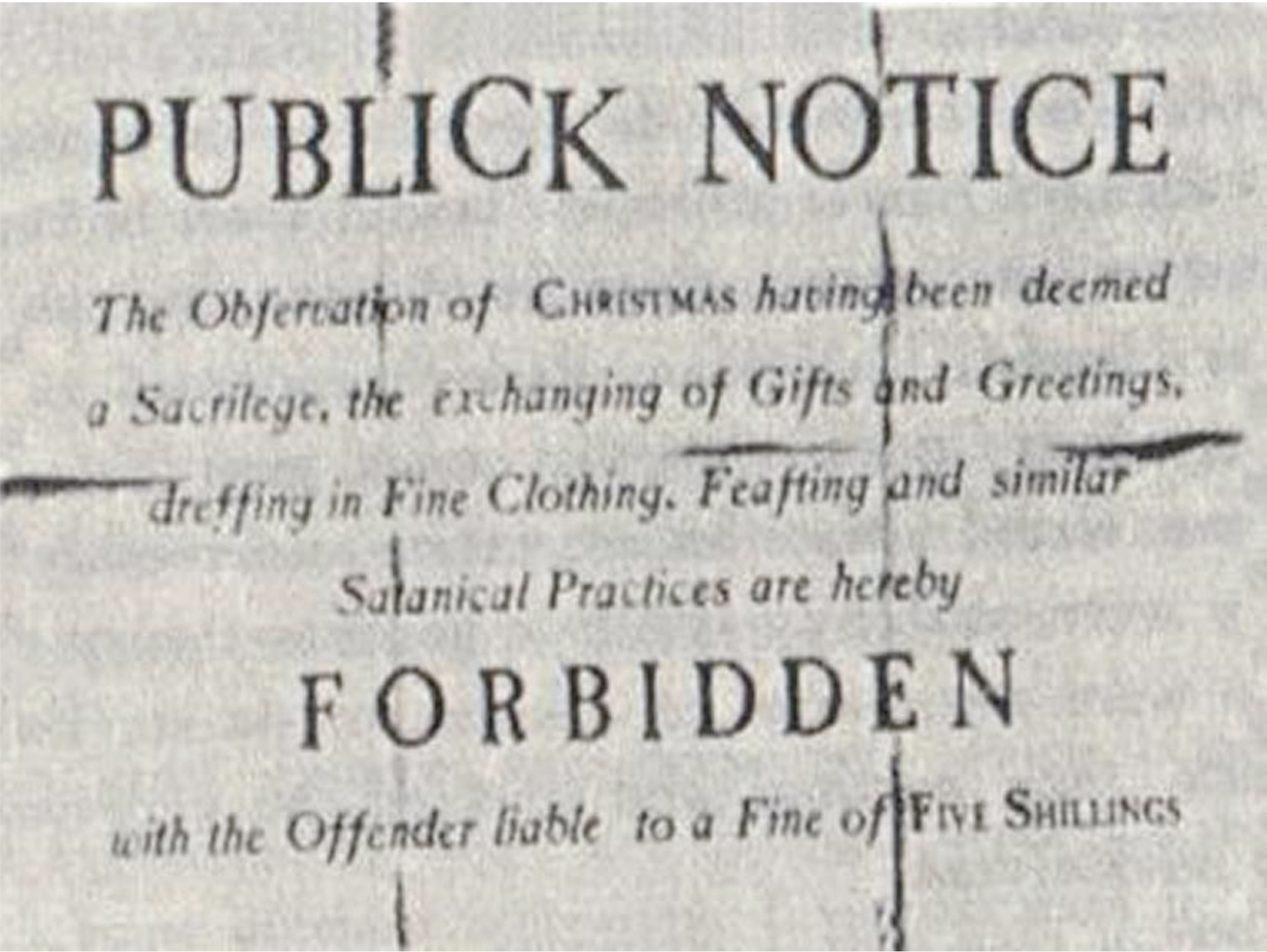

In 17th century Britain, Christmas could get you killed. Christian opposition to Christmas was one of the factors that led to the English Civil War. The Puritans wanted to purify the church of everything they saw as Popish or pagan — and Christmas was one of their targets. Meanwhile in Scotland, the Presbyterians found Christmas so unbiblical that they suppressed it as early as 1583. King James, I actually had to force Scotland to reinstate Christmas through military force, and two decades later the Scottish Church banned Christmas again!

When Civil War finally broke out in 1642, Oliver Cromwell’s fanatic Puritan forces quickly seized the country and soon Parliament declared that Christmas was no longer to be a feast, but a solemn day of fast and penance. In Canterbury and other towns, pro-Christmas protesters rioted in the streets. They were put down harshly, and on Dec. 24 town criers walked the streets of London calling out “No Christmas! No Christmas!”

Now that is, quite literally, a war on Christmas.[6]

In America, our Puritan ancestors left-liberal, tolerant Holland to come to the new world, where they would be free to practice their religion — by persecuting other people’s religion. They, also, made Christmas illegal. By the time of the American Revolution, our Founding Fathers were, for the most part, actually nominal deists, often accused of being atheists by their opponents, and sick of the religious strife that had torn apart Europe and the American colonies. Washington’s crossing of the Delaware was a sneak attack at Christmas time.

After the war, Christmas was associated with Tories and the Anglican church. The Congress treated the 25th of December as just another workday, and they would continue to pretty much ignore Christmas for the next 77 years.

In America and England, by the eighteenth century, Christmas was dying; wounded by Christians in centuries of conflict and bloodshed. And then, it was dead.

Christmas Returns!

But a half-century later, Christmas rose from the grave! A Christmas miracle largely thanks to one man: Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol wasn’t a particularly successful book - until he began reading it aloud at book tours. Then it became a breakaway hit; within a year, he was selling out to crowds as big as 35,000 clamouring to hear him read the story of Ebenezer Scrooge and Tiny Tim. Victorian families who hadn’t celebrated it in generations went out and bought their first-holiday turkey after reading A Christmas Carol.

More Christmas books came out to also become big hits, while depictions of Saint Nick and Father Christmas began to develop into our familiar Santa Claus. Queen Victoria, who was really descended from Germany, had always celebrated the holidays with a traditional German Tannenbaum. Now everyone started getting on the Christmas tree bandwagon. Many old forgotten customs were remembered, or half-remembered again. And while virtually all the traditions we now associate with Christmas actually came from pre-Christian pagan religious faiths, ironically so much of our contemporary Christmas doesn’t even come from those ancient traditions but were invented in the 19th century.

And new Christmas traditions, songs and characters, like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and Frosty the Snowman, kept appearing — along with the never-ending harangues that the holiday had become too commercial, too secular, and yes, that we had forgotten “the True Meaning of Christmas” — the complaint which has become one of the most beloved and enduring Christian Christmas traditions...

The Real Reason for the Season

But if there’s a true meaning of Christmas, we’ve never really lost it. Because honestly, there’s no wrong way to celebrate Christmas, or Hannukah or Kwanzaa, or any of the myriad ways we’ve created to honour the axial tilt of Earth’s orbit that gives us the Winter Solstice. Since the ebb of the ice age, we have been coming together to share with one other, to celebrate friendship and family, and to make a home for love and warmth in our hearts, no matter how cold or scary the rest of the universe outside may seem. Here’s wishing you all the best and happiest of holidays!

—David Fitzgerald

David Fitzgerald is the award-winning author of Nailed and The Complete Heretic’s Guide to Western Religion Series (including The Mormons and Jesus: Mything in Action). New episodes of his planksip video series, The Myth of Jesus with David Fitzgerald can be seen at: https://planksip.me/MythMan

But see Nailed and Jesus: Mything in Action for more details. ↩︎

The original gospel, Mark says absolutely nothing about Jesus’ birth or childhood, while John, the last canonical gospel, twice mentions that Jesus is the son of Joseph (1:45, 6:42) without any further clarification. ↩︎

For example, see the scholarly sources cited in Nailed and Jesus: Mything in Action. For just some of the more prominent current titles from just a few qualified scholars, see Dr. Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus and Proving History, Dr. Robert M. Price’s Deconstructing Jesus and The Incredible Shrinking Son of Man (in addition to many other works), Dr. Raphael Lataster’s Jesus Did Not Exist and There Was No Jesus, There is No God; see also the anthology The Varieties of Mythicism, ed. By Price & John Loftus. ↩︎

Though as it turns out, the evidence for the “real” St. Nicholas turns out to be rather questionable, too. See David Kyle Johnson’s The Myths That Stole Christmas, and Tom Flynn’s The Trouble With Christmas. ↩︎

Even in parts of the United States, the Julebukking tradition survives today. See:

https://www.tptoriginals.org/terrific-or-terrifying-a-primer-on-the-scandinavian-tradition-of-julebukking/ ↩︎For more, see: https://www.historyextra.com/period/stuart/no-christmas-under-cromwell-the-puritan-assault-on-christmas-during-the-1640s-and-1650s/ ↩︎