No Reason

This is a fairly deep dive into the message of radical non-duality, and some of the more exasperating and enduring questions it gives rise to. Definitely not easy going, or in any way useful. You’ve been warned!

Everything our senses tell us is a constantly-evolving conjecture, a model that the body’s nervous system (which includes the brain) conjures up to ‘represent’ reality. It does this to try to protect the entire body and the complicity of cells, organs and tissues that our ‘selves’ call ‘us’. So when it ‘sees’ a tiger, it correlates the colours (the wavelengths of light reaching the eyes) and the speed (the apparent ‘movement’ of those wavelengths through time and space) with its memories of similar ‘occurrences’ in the ‘past’. (Time and space are also the nervous system’s inventions, place-holders or categories or features that it uses to make sense of things.)

The senses are the means by which our nervous system converts quanta (bits of energy) into qualia (usefully distinguishable features) — what we call ‘perceiving’. There actually is no such thing as colour or speed — these are just qualia that our brains and nervous system ‘make’ of things.

You may accept that colour and other visual perceptions are just concoctions of the nervous system. But you may be less willing to accept that the apparent solidity of a wall is likewise an invention of the nervous system. After all, when we walk into a wall, we don’t just ‘perceive’ it to be solid and impenetrable, we know it is.

But in fact, this is a false distinction between our touch perceptions and perceptions of the other four senses. The feeling of impermeability of a wall is just another qualia — no less of an ‘illusion’ (or perhaps ‘allusion’) than what we see.

We ascribe ‘reality’ to something we see when we confirm it through the sense of touch. A startlingly realistic hologram we cannot touch is not ‘real’, while anything we touch in a completely dark place is ‘real’. We even use the word ‘tangible’ (something that responds to touch) as synonymous with ‘real’.

But if we look closely enough at anything we think of as ‘physically’ real (like a wall), we discover it is made almost entirely of nothing, and if we move in and look closer at what seems not to be nothing, we find that, too, is almost entirely nothing, and so on, ad infinitum, until we must conclude that nothing is real, and that our touch-perception of the wall as ‘real’ is no more validating than the sight-perception of colour.

Everything we think of as ‘real’ is just a perception of the nervous system, a representation or map of what we then conceive of as ‘really real’. Nothing is ‘really real’. Everything is just nothing, appearing to the senses as quanta, which are converted by the senses into qualia, which the nervous system then uses in its totally fabricated model of ‘reality’.

In short, we don’t ‘know’ the wall is solid and therefore ‘real’ — we ‘feel’ it to be so, and then define it as so accordingly.

We also think of thoughts, feelings, and our ‘selves’ as ‘real’ although we cannot touch them ‘physically’. Thoughts and feelings are merely another form of electrochemical signal, more qualia, the only difference being that we distinguish them, completely arbitrarily, as being ‘inside’ ourselves. But this doesn’t bear scrutiny either. How is a sore wrist substantively different from a feeling of sadness or a thought about something being good or evil or correct or wrong? We distinguish them by ascribing our pains as being ‘our body’s’ while the thoughts and feelings are ‘ours’ — by which we ambiguously mean they ‘belong’ to our nervous system, our brain, or our ‘conscious self’.

They are all sense-making, attempts to cram all the qualia into the model, the story of ‘us’, no matter how badly they may fit. They are all inventions, fictions. Unreal.

But rather than trying yet again to unravel the illusion of the self, let me try a different tack: Scientists like Stephen J Gould and Richard Lewontin have argued that nothing is actually separate from anything else, that not only are there no distinct, separate “things”, there is no border or real distinction between anything and its environment. Our environment is as much a part of us as we are part of it. All there is is this great flurry of energy, some of it appearing as matter, and any borders we conceive between some of it and the rest of it are just mental conventions, with no scientific basis in ‘reality’.

What’s more, our conception (it is not a perception) of time, of there being continuity and consistency and predictability, is also just another kind of sense-making, categorizing, model-building. Our nervous system invents the ideas of past, present and future, because they seem to be useful representations of what seems to be happening, and then it tells a story about things happening ‘in’ and ‘over’ time.

But even the most conservative scientists now agree that time is not fundamental to our understanding of the universe and ‘reality’. Science can explain things far more simply without reference to there being something ‘real’ called time, than they can when they do reference it. Einstein acknowledged this as well, while agreeing that time is just “a persistent and convincing illusion”. Things appear to happen ‘in’ and ‘over’ time, but that’s just a story, not based in reality. Like colour, it can seem to be a useful construct, but we do tend to mistake our constructs (the map) for reality (the territory).

Without separate ‘things’ and without real ‘time’, the fiction of our ‘self’ becomes more apparent. Neuroscientists have concluded that the self is not identifiable with any parts of the brain, nervous system or body. It is merely another construct, an invention of the nervous system that serves conveniently as a centrepiece for the complicated model of reality that the nervous system has conjured up.

We assess whether something is real or not based on what our senses tell us. In addition to the five perceptual senses, we (perhaps uniquely) have also evolved conceptual senses. These are ‘false senses’ that allow more of what the nervous system is trying to process to fit (though badly) within the model. We ‘sense’ thoughts and feelings, even though they have no perceptual foundation. Our thoughts and feelings are, therefore, false senses, conceptual senses. We take ownership of them as ‘ours’ just as we do ‘our’ perceptions. They are false in the sense that they are fictional senses, entirely made up and purely reactive, without any reference to perceptual signals. There’s a reason we use the word ‘sense’ to describe all these seemingly-different things.

Likewise, our sense of self is a false, conceptual sense. Like thoughts and feelings, the self is not a translation of our five senses’ signals from quanta to qualia. It is a total fabrication, a ‘figment of reality’, made up as a conjecture because it seems to fit with the very muddled and insanely complex model of reality that the nervous system has constructed to try to make sense of all the signals coming to it.

To sustain its credibility, the nervous system now has to ascribe free will, responsibility and control over the body to this self, this complete fiction it has constructed. The only way it can possibly do so (since the body will do what it will do, based on its conditioning and completely indifferent to the self’s preferences and instructions), is to rationalize everything that the body does, and all the thoughts and feelings it arrogates to the self, as being the self’s volition.

This is quite a preposterous and exhausting undertaking, since there is such a massive cognitive dissonance between what the self has figured out ‘should’ be done according to the model, and what the body goes ahead and does anyway. No wonder we are all swimming in guilt, shame, grief, and ‘self-doubt’!

But it’s the best the nervous system can do. Its hopelessly flawed model of reality is the only tool it has to do its job, which is to be what Stewart and Cohen call the ‘feature detector’ for the body. With the expanded brain, the human self has expanded its self-importance such that it sees its role as the protector and decision-maker for the body, when it is (and can be) nothing of the sort.

Other animals are not plagued with this disease of the sense of a separate self. They are, and sense themselves to be, from what we can understand, simply a part of everything-that-is. Their instincts, not abstract inventions of their nervous systems, protect and guide them, and have done so perfectly well for billions of years. They don’t suffer from the delusion of self-control, and have no need to try to rationalize (and beat themselves up over) the gap between what their self thinks ‘should’ have been done, and what their body did.

_____

In radical non-duality circles, a distinction is often made between what is apparent and what is illusory. Their observation is that nothing is ‘real’, or ‘unreal’ in the sense we usually use those terms. Everything is an appearance of nothing, and nothing is separate. Nothing can be known. It requires no ‘consciousness’, and no perceiver, for this to be obvious. This is of course unfathomable, unbelievable, to selves who perceive themselves and their bodies to be real and separate, and who perceive life and ‘consciousness’ to be prerequisite for anything to ‘appear’ at all. Hence our fear of the death of the body, for which, absurdly, the self feels responsible.

If everything is apparent, what then is illusory?

Radical non-duality says it’s obvious that only the self is illusory. And as the self is illusory, the idea that thoughts and feelings and anything else belong to the self is likewise illusory. Thoughts and feelings can apparently arise, but they are not ‘anyone’s. Things involving bodies can appear to happen in space and time, but they are not ‘really’ happening and there is no ‘real’ space or time in which they are actually happening. This cannot be known or understood, because there is no one, no thing separate, to know or understand anything.

Evolution, and other happenings that seem to have patterns and causality and consequence may appear to be happening, but there is no real time in which they can happen, so they are all just appearances. Preferences and proclivities that seem persistent characteristics of some apparent bodies can also appear, but they are just appearances. They need no self to inculcate those preferences and proclivities, and no self is needed for their appearance to be obvious.

The conditioning, biological and cultural, that seems to be happening is, again, just an appearance, a story that needs no viewer or believer to be seen. It makes no more sense, and needs not make any more sense, than the growth of ice on a window in winter in gorgeous fractal patterns ‘needs’ to make sense, needs an explanation.

For me, the most dissatisfying part of the paradox of the self is the observation that when the illusory self apparently disappears in some apparent people (sorry, that’s a maddening phrase, but it’s necessary to make the point), the apparent person/character that is apparently ‘left’ seems to be, somehow, less neurotic, more relaxed, and less motivated than ‘before’. How can that be if the self is purely illusory?

Friends who have ‘lost’ their sense of self and separation seem unperturbed by this question, and though they offer no answer, they’re not being evasive. One of the things I’ve learned from listening to a million questions about radical non-duality is that there are no direct answers to any question about it, as it can’t be known. You can describe what “this” isn’t but not what it is.

So the standard questions about it are generally answered, earnestly and as carefully as possible, as follows:

- Who…? questions — There is no one.

- What…? questions — Nothing appearing as everything.

- When…? questions — There is no time.

- Where…? questions — There is no separateness, no separate places, no movement in space.

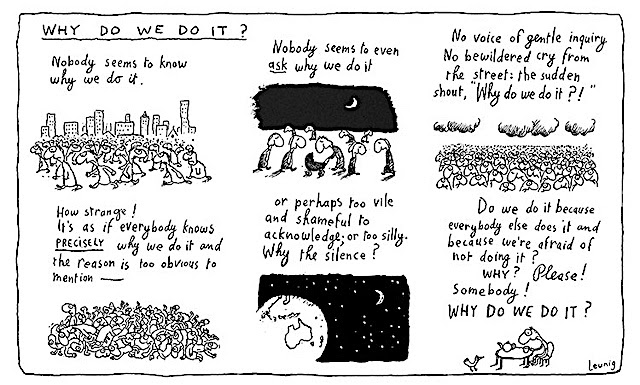

- Why…? questions — There is no reason, no meaning and no purpose for anything.

- How…? questions — There is no causation, just what’s apparently happening, for no reason.

So: How can a purely illusory self seemingly affect the apparent character that it presumes to inhabit? The question has neither meaning nor answer. It’s just what is apparently happening. Less neurosis seems to be what is happening, but since there is no real time in which there can be ‘more’ or ‘less’ of anything, it’s just an appearance, like evolution, or getting older and dying.

Without the self, the paradox simply disappears. There is no one, and nothing ‘really’ happening. And never has been. There is no need of any one, or of any thing to happen. And never has been. No further explanation is needed, but to the self, this explanation can never be satisfactory. It can never make sense. “No no no”, says my self, “that can’t possibly be right! It leaves me with nothing to do, and strips me of all my accomplishments and knowledge. Keep looking for a better answer!”

And of course, I am.

Finding the Sweet Spot: the natural entrepreneur's guide to responsible, sustainable, joyful work

"Now what am I going to do?" is a question many people ask—and leave unanswered—at critical potential turning points in their careers. Perhaps you’re a new graduate, but instead of lining up for a boring entry-level job at a big corporation, you wish you could start your own sustainable and responsible business