Credulous

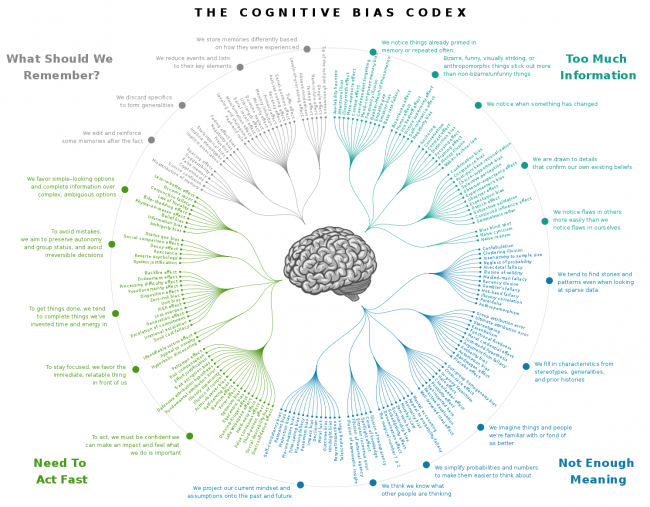

The cognitive bias codex from Wikipedia; right click and open in a new tab to view legibly; or view and print the original over four letter-sized pages and paste them together. The model was developed by John Manoogian III and refined by Buster Benson; the online version includes links by TillmanR to the wikipedia articles explaining each bias.

What is it that makes some people, and the members of some cultures, more willing and ready to believe what they’re told than others? There’s some indication that we tend to believe the opinions of people we know well and trust the most — even if they’re as ignorant as we are about the facts. At one time (eg Watergate, Clinton) getting caught in a lie irretrievably damaged your credibility, but as propaganda has become more and more widespread, that may no longer be the case.

Opinion polls (themselves highly suspect) suggest that we trust just about all sources of information — politicians, economists, the media, lawyers and doctors and consultants and other “experts” — less and less. In particular, we’re getting increasingly suspicious of what “sources” are not telling us (lies of omission), not just about what they are reporting.

Yet we still seem astonishingly credulous, particularly when it comes to reported events we cannot personally witness because they are happening on the other side of the world (or at least allegedly happening). So we’re more prone to be “played” both by the slick propaganda operations of moneyed and motivated interests, and by conspiracy theorists who exploit our increasing suspicion of “official narratives”. As a result, most of us no longer know what to believe.

I grew up in the 1960s, when the Cold War was raging, the Cuban missile crisis threatened imminent nuclear war, and the McCarthy witch hunts were still in recent memory. I learned to get my news from shortwave radio and the often-raided and censored workers’ news-shops in Winnipeg’s north end. My father was a journalist, so I knew how the system worked (He quietly sheltered Vietnam War conscientious objectors who’d fled the draft). I was bombarded with propaganda from all sides, everything from pro-Apartheid broadcasts from South Africa to broadcasts adulating Mao and his anti-intellectual purge. I listened to the Voice of America and its relentless pro-war, anti-communist harangues that broadcast 24/7 in sixty languages.

I managed, once, back in the day, to wangle an invitation to a press conference held by James Richardson, then Canada’s Minister of Defence, shortly after the US National Guard murdered four unarmed protesters at Kent State, and after the leak of the Pentagon Papers, which today would almost certainly be grounds for the incarceration or “disappearance” of the offending journalists. The Vietnam War was still being escalated. Four million would eventually die in that insane 30-year-long war. After the conclusion of the press conference, I asked the Defence Minister about the government’s policy on dealing with climate change, and particularly about the proposed Mackenzie Valley Pipeline, and its prospective impact on the arctic environment. His answer was simple and terse: “Who cares about the permafrost?” He was then hustled away by his handlers before the press heard him raising his voice at me. I tore up my membership in the Liberal Party that day. The next day, his boss, PM Trudeau the Elder, gave a speech about the importance of protecting the environment.

Back then, as now, what I did not know about was as notable as what I did know (or thought I did). Like almost all citizens, I knew nothing about the US involvement in destabilizing and overthrowing a dozen governments in Latin America and at least as many in Asia, the Mideast and Africa. I knew nothing of the Canadian government’s complicity in US wars, surveillance, and propaganda campaigns. I knew nothing about the extent to which corporations, industry groups, foreign political groups, the “intelligence community” (the propaganda arm of the military-industrial complex), and ideological interest groups lobbied, bribed (there really is no other word for it), threatened, wrote legislation and press releases on behalf of, and otherwise corrupted governments and the political process in every country in the world, almost always against the interests of their citizens. I knew nothing about the revolving doors of the military-industrial complex (a term coined by Eisenhower, hardly a lefty, who was fearful of its potential power and influence) between corporations, lobbyists, government bureaucrats, and politicians across the political spectrum.

I was credulous. I keep learning that I still am credulous, that I allow people I know and trust to convince me of things that are simply wrong. They’re not deliberately lying to me. They’re just as credulous as I am, inadvertently parroting outright misinformation in the genuine belief of its veracity.

So I have reached the point where I only tentatively believe anything, and I am inclined to challenge everything I’m told. I am suspicious of anecdotal “evidence” whose purpose seems most often to undermine the credibility of the greater preponderance of evidence, when that can even be known.

I tend to be least suspicious of reportage that encourages us to believe that the issue is extraordinarily complex, that takes the time to explain the history and context behind the issue in nuanced terms, and which rather than taking sides asserts that everyone is doing what they think is right, that every action is understandable if one makes the effort, that there are no “good guys” or “bad guys”, and that some seemingly-incompatible statements about an issue can both be correct, such as this list from former British Ambassador Craig Murray:

a) The Russian invasion of Ukraine is illegal: Putin is a war criminal.

b) The US led invasion of Iraq was illegal: Blair and Bush are war criminals.

a) Russian troops are looting, raping and shelling civilian areas.

b) Ukraine has [ultra-nationalist, hate-mongering] Nazis entrenched in the military and in government, and commits atrocities against Russians.

a) Zelenskyy is an excellent war leader.

b) Zelenskyy is corrupt, and an oligarch puppet.

a) Russian subjugation of Chechnya was brutal and a disproportionate response to an independence movement.

b) Russian intervention in Syria saved the Middle East from an ISIS-controlled jihadist state.

a) Russia is extremely corrupt with a very poor human rights record.

b) Western security service narratives such as “Russiagate” and “Skripals” are highly suspect, politically motivated and unevidenced.

a) The Russian military-industrial complex is powerful [and dangerous] in its own [sphere of influence], as is Russian nationalism.

b) NATO expansion is unnecessary, threatening to Russia and benefits nobody but the military-industrial complex.

The full article linked above explains in almost excruciating detail why the (a) and (b) statements in this list can both be true, and what that means for the sorry state of our understanding of the world and the dangers of one-sided perspectives, which are almost always rife with mis- and disinformation.

We want things to be simple; I get that. But they’re not. It takes time and energy to tease out the complex truth about what’s happening right now in Syria, in China, in Yemen, in Ethiopia, in Venezuela, in Palestine, in Cuba, in Afghanistan, and in dozens of other countries in economic, social, ecological and political free fall. This is especially true when there are vested interests that don’t want you to know what’s going on. Since most of us have neither the time nor the energy to study them, and to separate the truth from the mountains of propaganda, mis- and disinformation, we are paralyzed into inaction and ignorance. Or, perhaps worse, we are credulously propelled into buying one simplistic and partisan perspective that plays right into the hands of those who benefit from it.

I was going to make a list of some of the things I was credulous about, at various stages of my life, to my great embarrassment. But the list is rather depressing, and what’s more important, I think, is to understand why I was (and still am) so credulous. Here are some of the reasons I came up with:

- The deception fit well with what I previously knew (or thought I knew) and was already inclined to believe.

- The person who deceived me had not, to the best of my knowledge, deceived me before, even unintentionally.

- The person who deceived me was very passionate (but in an engaging, not an out-of-control way).

- The person who deceived me was very articulate, and sounded dispassionate — they had no apparent reason to want to deceive me.

- The person who deceived me clearly honestly believed what they were telling me.

- The person who deceived me cherry-picked the “evidence” they gave me, or it had already been cherry-picked for them when they learned of it.

- The deception was not about a subject that was particularly important or urgent to me, so I was less concerned about its veracity than I might otherwise have been.

- Multiple people, who were not obviously drawing on the same evidence or source, related the same deception to me.

- I actually participated in deceiving myself by filling in gaps in what the person deceiving me had actually said, in my zeal to make sense of what they had said.

- I felt it was important to have some position or opinion on the subject, for a variety of reasons, so I was amenable to a possible deception in the absence of other data, evidence or arguments.

This is so human (as the chart above, which reveals the cognitive failures behind each of the above reasons, illustrates). And it is so human to exploit these failures when deceiving (deliberately or not) other people. We want people to believe what we do. We want people to reinforce our own beliefs. We want to feel knowledgeable, and informed.

I am picturing a tribe of very early homo sapiens, living together even before the advent of language that enables us so treacherously to deceive. They are calling and signalling to each other. A member of another tribe has been spotted, they signal, an invader in the tribe’s territory. What will determine what they believe, now, and hence what actions they take? Will it be based on the truth, the evidence, or on their predisposition as to what they are already inclined to believe, or even on some deceit, intentional or not?

Such credulousness seems to have been evolutionarily selected for in our species, and maybe in most species. This leads to faster decision-making, and hence faster, more decisive, less hesitant, less divisive action. I guess that works, in terms of survival.

But at such a cost.

Finding the Sweet Spot: the natural entrepreneur's guide to responsible, sustainable, joyful work

"Now what am I going to do?" is a question many people ask—and leave unanswered—at critical potential turning points in their careers. Perhaps you’re a new graduate, but instead of lining up for a boring entry-level job at a big corporation, you wish you could start your own sustainable and responsible business