Collapse: How’s It Going to End?

He had three whole dollars, a worn out car, and a wife who was leaving for good.

Life’s made of trouble, worry, pain and struggle;

She wrote ‘good bye’ in the dust on the hood.

They found a map of Missouri, lipstick on the glass;

They must’ve left in the middle of the night.

And I want to know the same thing everyone wants to know: How’s it going to end?

Behind a smoke colored curtain, the girl disappeared;

They found out that the ring was a fake.

A tree born crooked, will never grow straight;

She sank like a hammer into the lake.

A long lost letter; an old leaky boat — promises are never meant to keep.

And I want to know the same thing we all want to know: How’s it going to end?

The barn leaned over; the vultures dried their wings;

The moon climbed up an empty sky.

The sun sank down behind the tree on the hill;

There’s a killer and he’s coming through the rye.

But maybe he’s the father of that lost little girl; it’s hard to tell in this light.

And I want to know the same thing everyone wants to know: How’s it going to end?

Drag your wagon and your plow over the bones of the dead

Out among the roses and the weeds.

You can never go back, and the answer is ‘no’,

And wishing for it only makes it bleed.

The sirens are snaking their way up the hill;

It’s last call somewhere in the world.

The reptiles blend in with the color of the street;

Life is sweet at the edge of a razor.

And down in the first row of an old picture show the old man is asleep as the credits start to roll.

And I want to know the same thing we all want to know: How’s it going to end?

— Tom Waits (brilliantly sung by Lissa Schneckenburger)

Our civilization’s collapse is accelerating. You can see it in the increasing number of extreme, and now very extreme, weather events. You can see it in rising political and social intolerance, belligerence, and rage. You can see it in the runaway melting of the poles from unprecedented heat waves. You can see it in the slide of more and more countries into insurrection and fascism. You can see it in the rapid degradation of our soils, our fresh water, and our marine life. You can see it in the endless price bubbles and the growing skittishness of investment and real estate markets.

You can see it in the growing anomie and acedia of the majority of the population, especially young people. You can see it in the soaring rates of animal and plant extinctions. You can see it in the number of failed states, caught in an ever-growing spiral of corruption, massive inequality, political instability and crushing debt. You can see it in the erraticism and near-collapse of the jet stream, of the ocean currents, and the other eternal ecological cycles that have kept the climate in such extraordinary equilibrium these last few millennia.

You can see it in the ratcheting up of everything to try to keep it together: hydrocarbon production, military spending, debt levels, militarization of the police and security apparatus, magical thinking, the blame game, xenophobia, outsourcing and offshoring, dollar stores replacing grocery stores, the 24/7 firehose of propaganda.

David Ehrenfeld, in his book Beginning Again, thirty years ago, provided a glimpse of what the final stages of collapse might look like:

There goes a chunk — the sick and aged along with the huge apparatus of doctors, social workers, hospitals, nursing homes, drug companies, and manufacturers of sophisticated medical equipment, which service their clients at enormous cost but don’t help them very much.

There go the college students along with the VPs, provosts, deans and professors who have not prepared them for life in a changing world after formal schooling is over. There go the high school and elementary school students, along with the parents, administrators and frustrated teachers who have turned the majority of schools into costly, stagnant and violent babysitting services.

There go the lawyers and their hapless clients in a dust cloud of the ten billion codes, rules and regulations that were produced to organize and control an increasingly intricate, unorganizable and uncontrollable society.

There go the economists with their worthless pretentious predictions and systems, along with the unemployed, the impoverished and the displaced who reaped the consequences of theories and schemes with faulty premises and indecent objectives. There go the engineers, designers and technologists, along with the people stuck with the deadly buildings, roads, power plants, dams and machinery that are the experts’ monuments.

There go the advertising hucksters with their consumer goods, and there go the consumers, consumed with their consumption. And there go the media pundits and pollsters, along with all those unfortunates who wasted precious time listening to them explain why the flywheel could never come apart, or tell how to patch it even while increasing its crazy rate of spin.

The most terrifying thing about this disintegration for a society that believes in prediction and control will be the randomness of its violent consequences. The chaotic violence will include not only desperate ruthless struggles over the wealth that remains, but the last great violation of nature. What will make it worse is that, at least at the beginning, it will take place under a cloud of denial and cynical reassurances.

Sounds pretty close to what’s happening now, no? Collapse happens slowly, and then suddenly. We are watching the “slowly” part, as the water seeps into civilization’s sandcastles and some of the turrets start to tumble. Most of what is happening, we don’t see. It’s larger than us, more complex than we can understand.

But, as I have said before, there will be no Mad Max Hollywood endings to this civilization. “Suddenly”, in earth terms, means decades, not days.

So: How’s it going to end? Everything I have learned tells me there will be waves of collapse, with brief respites in between when we might imagine things could return to “normal”. Everything I have learned tells me that we will adapt (ie make permanent changes to how we live) better than we might think, but that “resilience” (ie trying to “bounce back” to the way things were) is an ill-conceived strategy. And everything I have learned tells me that much of the world is already suffering from civilizational collapse, and we would be wise to pay attention to what’s happening there and how their citizens are coping with it.

But I am starting to change my mind about how gracefully we are going to manage the bumpy descent.

My grandparents told me about the Great Depression riots, the hunger, the despair, and how, when there was no other choice, everyone started to get along and work together. They introduced graduated taxes where the rich, and corporations, paid 90% tax on their income and profits, because there was no other choice. They introduced debt ‘jubilees’ so that suddenly, no one had a negative net worth, and people who couldn’t afford to eat or to clothe their children were rescued from starvation and destitution, because there was no other choice. People took in homeless strangers as boarders, left their abandoned homes to whoever next migrated past them, asking only that each occupant leave them the way they found them, because there was no other choice.

But now, it seems, there is another choice: To shoot the poor, the sick, the homeless, immigrants desperate for food, people who “aren’t like us”. Or to blame them, the victims of our civilization’s excesses and ruthlessness and unsustainability, for their misfortune, or deny it altogether, surrounded by other deniers who reinforce our denial.

At what point will we run out of these ‘other choices’ and start to behave like communities, tribes, real humans again? That is the big question in any collapse scenario, in describing how it will play out, and how it’s going to end.

To attempt an answer to the impossible question How’s it going to end? requires first some conjecture on how long the current collapse, our descent into ‘uncivilized’ humanity, will take. In his novel A Scientific Romance, my fellow British Columbian Ronald Wright’s protagonist jumps five centuries into the future, and when he sees the world five hundred years hence, remarks:

The Glen Nessies of the earth may survive, human numbers may eventually rebuild, we may with time and luck climb back to ancient China or Peru. But the ready ores and fossil fuels are gone. Without coal there can be no Industrial Revolution; without oil no leap from steam to atom. Technology will sit forever at the bottom of a ladder from which the lower rungs are gone.

Ronald has also said that he loved Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, as did I. Russell’s book is set two millennia in the future. Both books envision a future that is, at least for its human survivors, based on a salvage economy somewhat like what Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s book The Mushroom at the End of the World (subtitled “On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins”) envisions. But Anna was not talking about the future, when the industrial economy has completely collapsed. She was talking about the present, in places where collapse is already nearly complete. These three books, I think, provide a bit of insight into what an ‘economy’ will mean after civilization’s collapse. It won’t be like what those of us who are only familiar with the Industrial Growth economy imagine.

This all assumes, of course, that the collective memory generations after the end of today’s declining civilization will continue to value and pass on skills related to technologies that no longer exist. I think, based on what I’ve read of previous civilizations, that that is unlikely. Once the scavengeable relics cease to have any clear relevance to the way of life of future societies, they will cease to be used, and cease to be part of future economies. We humans forget fast.

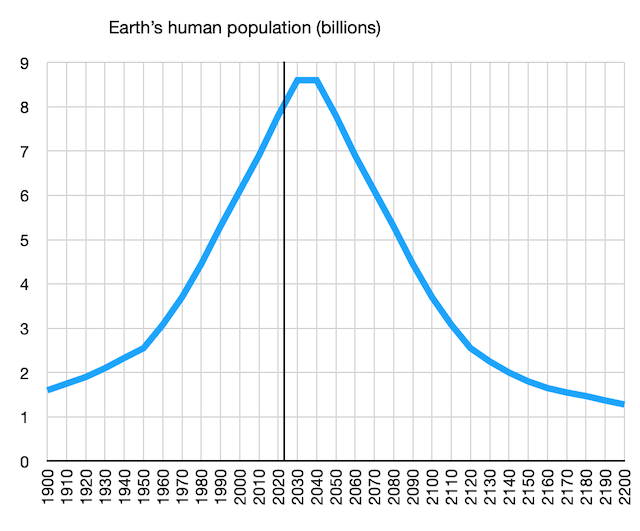

Our civilization arguably began about thirty millennia ago, with the invention of the spear and arrowhead that quickly launched the sixth great extinction of life on earth (starting with the great mammals), and since civilizations tend to follow ‘normal’ curves, rising and declining at about the same pace, then perhaps an appropriate time horizon for speculating on life at the end of human civilization, and on the question of How’s it going to end?, might be as long as 30,000 years from now. Though I think we’ll be able to see the end in sight as soon as 10,000 years from now, and perhaps even sooner.

I’ve laid out some scenarios before, but they are, I think, like most dystopian sci-fi and cli-fi, overly prone to presume that the future will be like the past, only more so, or in reverse. I’m going to quickly touch on how I think we’re going to navigate our way to the end of this civilization, though these guesses are almost certain to be wrong, possibly wildly so. But we are animals, after all, and not immune to the laws of nature. I think we might be able to make a passable guess about How it’s going to end, even though we have no idea how we’ll get there.

Nuclear annihilation is certainly a possibility, either through war or incapacity to keep the toxic waste from the world’s nuclear reactors safe and cool forever (such hubris we humans are capable of!) But it’s not a very interesting scenario to contemplate.

Neither is the prediction by some scientists that accelerating, runaway climate change will, sooner or later, make the entire planet uninhabitable by any form of complex life. They may be right; there are too many variables to say with any degree of certainty.

The scientific consensus is that between 1 CE and 1000 CE, human population was fairly stable at about 250 million. Even earlier, ten millennia ago, it was somewhere below 10 million. And before that, for the first million years of our existence, population varied from perhaps a few thousand (during the Toba Catastrophe) to about a million. Back then, we were always an endangered species.

So we might envision the human population decreasing to about 250 million, by 1,000 years from now, and then to about 20 million by ten millennia from now, and perhaps to just a few million by thirty millennia from now. The decline won’t be consistent or smooth, of course, but it’s likely manageable just by having a significant proportion of the population choosing to remain childless, which, if you’re a dystopian, isn’t hard to imagine.

Twenty million humans would not make us an endangered species. That’s the number of elephants that once thrived in Africa (there are fewer than 50,000 left now), and would seem to be a pretty good number for a potentially sustainable human population, even on a storm-ravaged and resource-depleted planet. Falling further to under five million would be another matter, though our numbers were that low for most of our brief time on this planet.

The hardest part of collapse will be the immediate post-peak period from about 2040-2100, with population halving to about 4B over that period. Economic collapse will almost certainly precede the various phases of ecological collapse, and will likely provoke what I’ve called the Great Migration, with perhaps 1B people on the move to avoid starvation, drought, economic and the resultant financial and political collapse. It’s just starting now. And perhaps there will be social collapse as well. Then accelerating ecological collapse will weigh in and add as many as another 1B or more migrants, as floods and storms wipe out many coastal and agricultural areas, and heat and drought and chronic water shortages add to the misery.

But we’ll get there, as I say, because most people will just cease having children in such a world. But there will be a lot of political and social instability, and quite possibly violence. A time of struggle, setbacks, and learning from our mistakes.

The next period from 2100-2150 will, I think, be the age of adaptation. By this stage we will necessarily be living with a permanent, chronic shortage of energy, so long-distance transport will have mostly ceased, and substantially all transport will move to muscle-power — on foot, on bicycle, by oar and sail, and perhaps on horseback. Just as during CoVid-19, where we have learned how to do without things we thought were essentials, we’ll learn to do without anything that requires hydrocarbons or importation. When we find “the lower rungs” of our oil-based-technology “ladder” are gone, we’ll find other ways to climb.

Population will likely continue down the slope to about 2B by 2150. But there still won’t be enough resources even for this number. Our whole economy is built on hydrocarbon energy, and while there will still be some left, it will be absurdly unaffordable to extract and refine. The largest unknown is how quickly accelerating climate and ecological collapse will render much of the planet uninhabitable, potentially making the Great Migration a continuing, and relentless, human endeavour.

Over the following century I think human population will drop below 1B, and by 3000 CE, a millennium from now, if we’re still around at all, I suspect it will have dropped to close to 250M. That will still likely be ten times more than the carrying capacity of our depleted planet at that time. So over the following ten millennia our population will likely fall another 90% to about 20M. And then we’ll be at a crossroads. I’d love to be there to see what we do. Still only a blink away in the cosmic arc of time.

So here’s just one scenario for human society 1,000, 10,000 and 30,000 years from now. I don’t think this scenario is dystopian. It focuses on how it’s going to end rather than the thousand paths our future fortunes may take to get there:

1,000 years from now — 250 million humans

A millennium ago, 60% of the world’s ~250M people lived in what is now East China, the Mediterranean/Mideast, or India. Another 20% lived in the Americas, mostly between the Mexican Gulf and the Andes. These were the richest agricultural areas of the time.

A millennium from now, the habitable areas will probably mostly be north of 45º — what is now Northern Europe, Russia, and Canada. Some coastal areas affected by sea-level rise flooding and severe storms, and the dry interior areas which will have become deserts, will not be habitable even in those northern climates, which will have become semi-tropical.

Just as we have mostly lost track of the languages, technologies and learnings of those who lived 1,000 years ago, it’s likely that those living 1,000 years from now will know little about how we lived. They probably won’t care. Because life will not be as easy as it was for some previous civilizations living in naturally advantageous (resource-rich) areas, it’s likely that languages will revert to being mostly oral, rather than written. The most resource-rich areas will still support settlements of several thousand people, but most of humanity is likely to be living a nomadic, subsistence life.

Reduced human concentrations and reduced travel will mean epidemic diseases will be rare, while the exercise of farm and hunter-gatherer work will reduce chronic diseases. But while knowledge of the causes of disease will likely be passed down from our time, the absence of pharmaceuticals, surgical tools and antibiotics (beyond simple soaps) will mean many more deaths from infections and accidents. And the renewed prevalence of large carnivores will mean that, despite the likely continued use of gunpowder, many humans will die by being eaten.

The need for constant movement in response to continued climate change will mean there will be little leisure time for most 31st century humans, and will likely mean that large settlements, and hierarchical societies, will be unlikely to arise or endure.

Daniel Quinn famously said that all animal populations (including humans) adjust to the availability of food and other essentials. So my guess is that, with resources still tight and habitable land getting tighter, humans in 3000 CE will still be hesitant to bring more children into the world, so population will continue to decline.

10,000 years from now — 20 million humans

Ten millennia ago, there were (most anthropologists believe) no human abstract languages. And, perhaps not coincidentally, there were few human settlements larger than about 1,000 people. Yet there was art, at least in places where resources were plentiful and life relatively easy.

If the future were like the past writ backwards, we might expect the same to be true ten millennia from now. But things rarely work like that. My sense is that we’ll keep oral languages alive, because they are such extraordinary and useful inventions. But if we’re crowded into an ever-diminishing habitable earth, on a planet that may have to wait aeons to be amenable to flourishing complex life again, my sense is that we won’t have the time or inclination for much creation — either art or babies.

But that assumes that runaway climate change, and its consequences in terms of earth’s biology, continue unabated. In his book The World Without Us, Alan Weisman speculates that nature’s adaptability may be much greater than we suppose, particularly in the absence of further human industrial interference. If this should happen, and more-than-human life on earth finds ways to flourish despite global warming, and despite the ongoing poisons of humans’ abandoned, leaked and exploding nuclear waste sites and petrochemical facility “alleys”, then it’s not impossible that millennia of life in retreat across the globe might cease and even reverse.

If so, it will not be our doing. But if it happens, a human population of 20 million or so might well be sustainable. The lower rungs of the oil-based technological ladder may be gone forever, but at this population, with a planet slowly healing all around us, we might discover that there is, finally, room to breathe and grow, that life once again is an adventure more than a struggle, and that there is a future to look forward to. What might we do with that opportunity?

30,000 years from now — ? humans

If the more pessimistic climate scientists are right, and all or almost all of the planet, sooner or later, becomes uninhabitable for humans without our civilization’s technological prostheses of oil-powered heat and cooling, agriculture and global trade, then there is no reason to believe the halving of human populations might continue indefinitely, until one day there are no humans left.

But if mother nature, despite all the abuse we have heaped on her for the last thirty millennia, demonstrates the degree of resilience to overcome that abuse and restore some kind of equilibrium to earth’s ecological systems, then there is reason to believe there may be a place for us, if we learn to behave, as a part of the wondrous interconnection of all life on this planet, for at least a second million years or so. Still not long in cosmic time that has seen green turtles coming ashore the same way for 400 million years. But a second chance to show we might be able to be a ‘fit’ species after all.

Only a guess, but it’s the best I can do. My instincts tell me that, after the (long, slow, bumpy) fall, there is at least a chance that humans may learn to behave, and be allowed to be part of the wonder of life on this little blue planet after all, instead of interlopers eternally doomed to try to dominate it and unknowingly manufacture its destruction.

After all, I want to know the same thing everyone wants to know: How’s it going to end?

Finding the Sweet Spot: the natural entrepreneur's guide to responsible, sustainable, joyful work

"Now what am I going to do?" is a question many people ask—and leave unanswered—at critical potential turning points in their careers. Perhaps you’re a new graduate, but instead of lining up for a boring entry-level job at a big corporation, you wish you could start your own sustainable and responsible business