The Minoan Civilization

Ancient Aegean Bronze Age Civilization

The Minoans — Europe’s first civilization.

Location of Crete, Greece and the Aegean Sea

The Minoan civilization thrived on the island of Crete and the smaller islands surrounding it, like the island of Thera to the north. The English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans named the civilization after the legendary Cretan king Minos, who was said to have kept a Minotaur monster in a complicated maze called the Labyrinth under his palace at Knossos. The Minoans are not Greek, but they are part of Greek history. The Minoans spread their ideas and art to the Greek mainland by trading with the early Greeks.

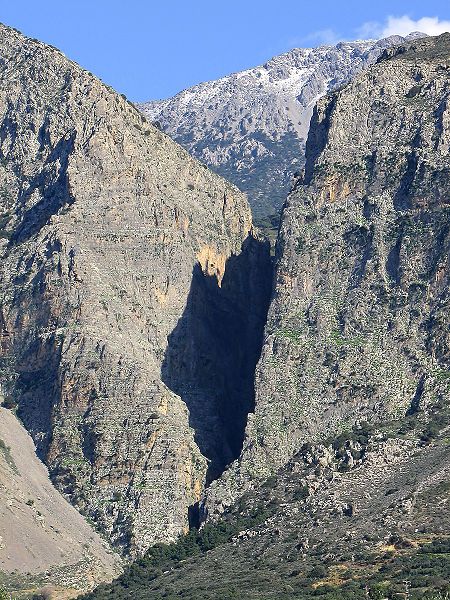

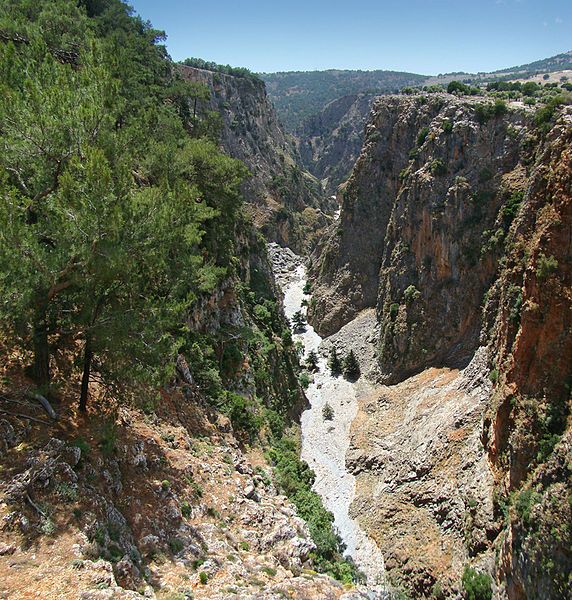

Crete is in the Mediterranean Sea, with the Aegean Sea on its northern shore. Crete is sometimes called the "stepping stone to the continents" since it is located within reach of Europe, Asia, and Africa by boat. Indeed, we have evidence that the Minoans traded with ancient people on all three continents. The Minoans had a surplus of olive oil, which they traded for Egyptian gold, copper from the nearby island of Cyprus, and tin from Turkey and Afghanistan. The Minoans were not only farmers of olives but also fine craftsmen who made pieces of jewelry, pottery, seals, and figurines. Their bronze workplaces this civilization in the Bronze Age.

At the height of their civilization, between 2,000 and 1400 BC, the Minoans developed a palace-centred civilization. The Minoan cities of Knossos and Phaistos are two examples of palace cities. Palaces acted as the economic and religious centers of the island. They were large and three to five stories tall. Interestingly, there were no defensive walls around palaces. The Minoans must have lived in peace on the island and relied on the sea and a navy for protection from outsiders.

Akrotiri was the largest settlement on Thera. A large volcanic explosion on Thera could have ended the Minoan civilization. However, the eruption also preserved the Minoan city of Akrotiri by covering it with volcanic ash, creating a kind of Minoan time capsule. Some people think that Thera was Plato's Atlantis, an advanced civilization that the Greek philosopher talked about being "swallowed by the sea." The Minoans had a high standard of living, and it shows in the ruins of the beautiful palaces and homes.

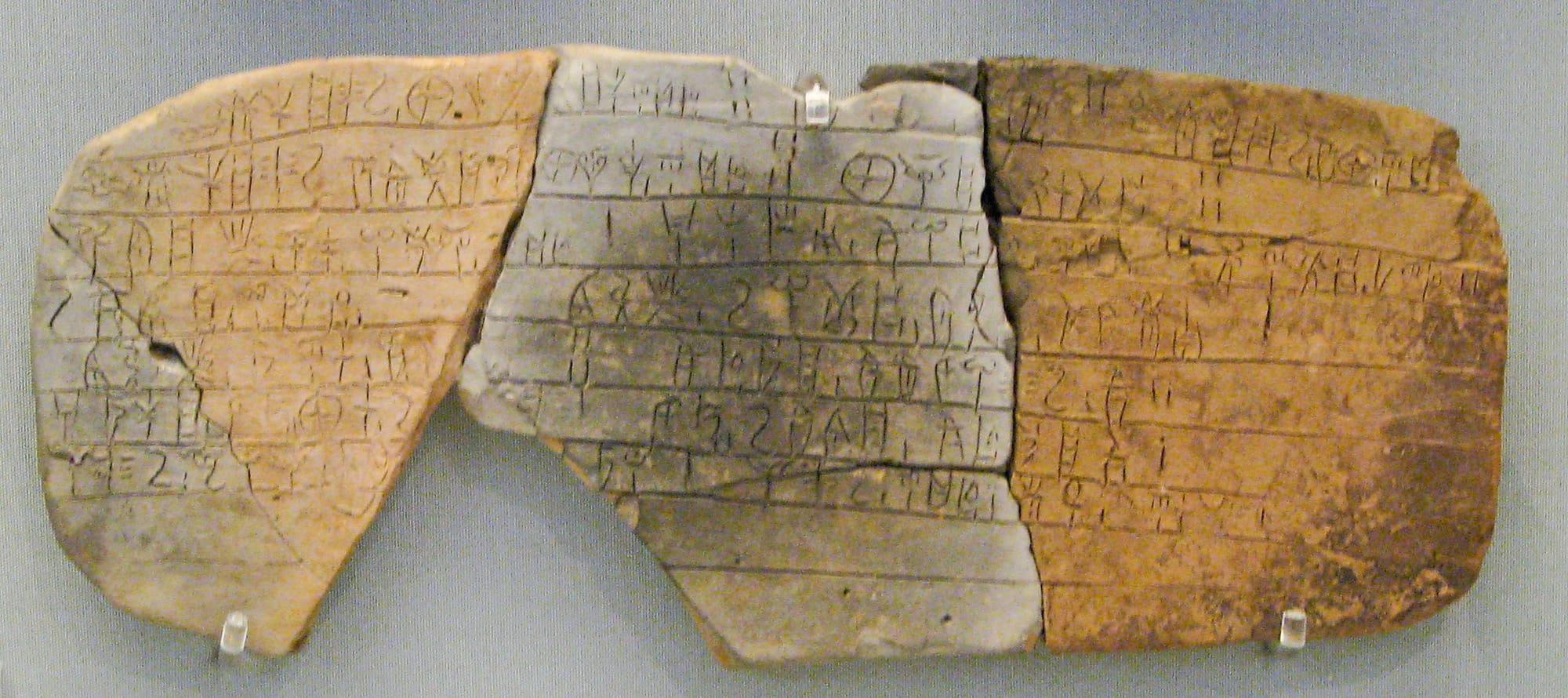

The Minoans had at least two different writing systems. The earlier is hieroglyphic, similar, but not the same as the Egyptian writing system. One example that has survived is the Phaistos Disc, discovered in the ruins of Phaistos. The later writing system is called Linear A. Linear A is written on clay tablets along lines, like our writing. No one has deciphered the mysterious Phaistos Disc or Linear A; therefore, the Minoan language remains a secret. One other script, Linear B, was also found on the island of Crete.

New Member Introduction - Join Today!

Without a written history, what we know about the Minoans comes from the artifacts and frescoes that have survived through the years. Frescoes indicate that men and women attended meetings and parties together; this suggests that women enjoyed equal social status to men. If this is true, the Minoans were far ahead of their time. The artwork also tells us that the Minoans enjoyed spectator sports. Both men and women attended and performed in these sporting events. The most popular and intriguing is bull-leaping.

The Minoan religion seems centered around a goddess, as many similar goddess figurines are found throughout Crete. She is sometimes called the snake goddess because her figurine holds two snakes in her outstretched arms. The bull seems to be important to the Minoan culture. People initially brought bulls to the island. The palaces of the Minoans have many carvings of the bull's horns. Another possible religious item is a double-sided axe called the labrys.

There is discussion as to why this advanced civilization disappeared. Natural disasters, including earthquakes and the volcanic explosion on Thera, caused a tsunami to hit the northern shore of Crete, but the civilization, though weakened, recovered. The invasion of the Mycenaeans, a warrior people, and the first Greeks seem to have ended the Minoan civilization.

The Mycenaean Civilization

Bronze Age Civilization on the Greek Mainland

The Mycenaeans are named after the city-state of Mycenae, a palace city and one of the most potent Mycenaean city-states. The Mycenaean civilization was located on the Greek mainland, mainly on the Peloponnese, the southern peninsula of Greece. The Mycenaeans are the first Greeks, in other words, they were the first people to speak the Greek language.

The Mycenaean civilization thrived between 1650 and 1200 BC. It was influenced by the earlier Minoan civilization on the island of Crete. This influence is seen in Mycenaean palaces, clothing, frescoes, and its writing system, Linear B.

Linear B

Linear B tablets were first found on the island of Crete; the writing was similar to the Minoan. Linear A. Arthur Evans credited the writing system to the Minoans. A young schoolboy, Michael Ventris, saw the Linear B tablets while touring the British Museum. Young Ventris was fascinated by the script, and when Arthur Evans told the class that the script had not been deciphered, young Ventris asked Evans to repeat what he had just said. Hearing these words a second time, Ventris decided that day that he would be the one to decipher this ancient script.

Ventris became an architect but never lost his passion for Linear B. Ventris could speak many different languages fluently and pick up a new language quickly. In 1939, American archaeologist Carl Blegen found several tablets of Linear B on the Greek mainland in the Mycenaean ruins of Pylos. Assuming that the language of Linear B was Greek, Ventris made a breakthrough in the early 1950s with the help of others working on the script, including American archaeologist Alice Kober. This made Arthur Evans angry because he was sure it was a Minoan script (Evans died in 1941. However, he was unhappy with any theory, up until then, that Linear B was anything but Minoan writing). The Mycenaeans used Linear B to keep records of their trading and economy. Unfortunately, the writing was not used to tell stories or show feelings.

How the later Greeks felt about the Mycenaeans

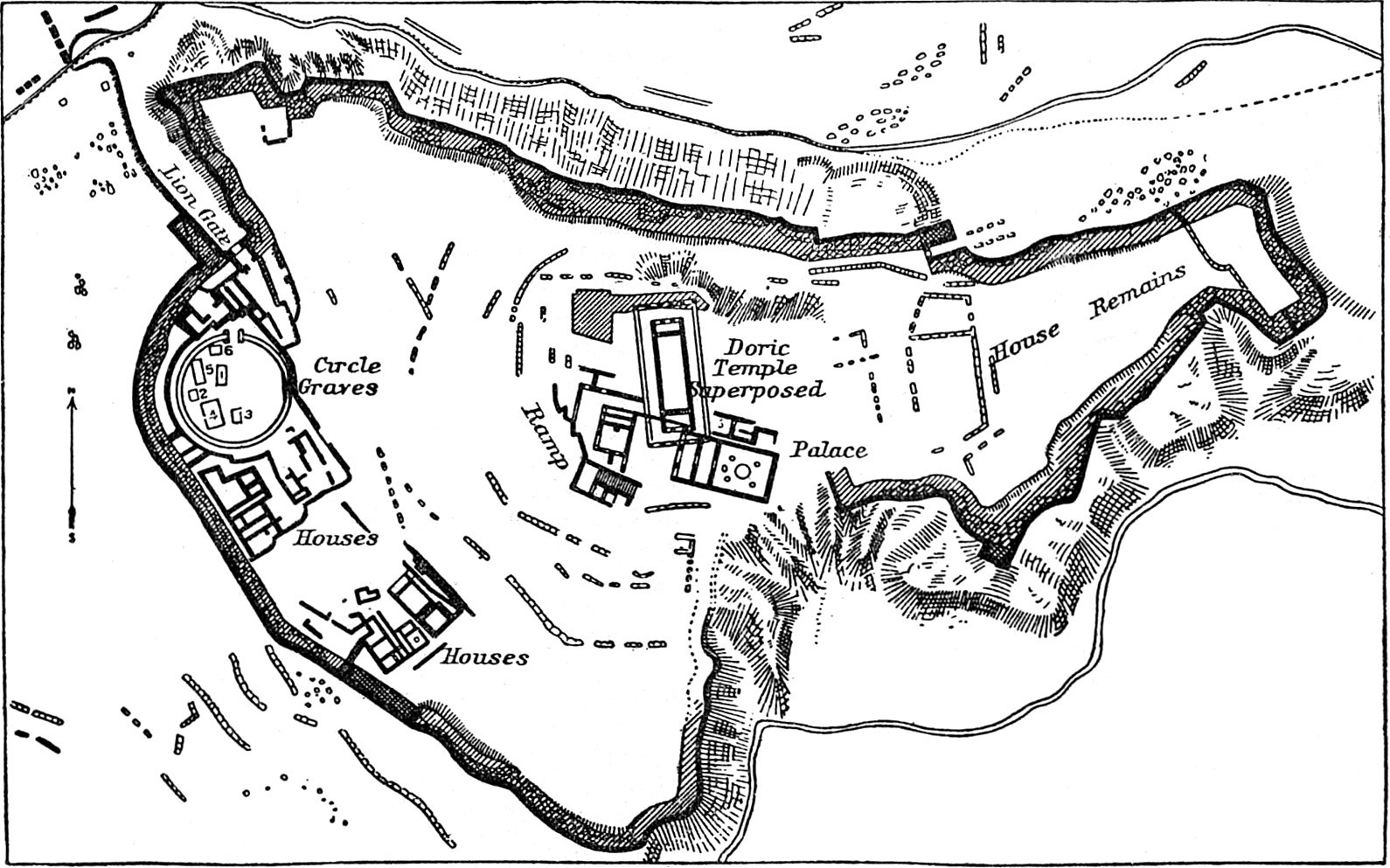

The later Greeks told stories about the Mycenaeans who preceded them, like the poet Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. In the eyes of the later Greeks, the Mycenaeans were larger than life. One reason for this belief comes from the ruins of the Mycenaean city-states. The walls around these palaces are massive, made from blocks of stone weighing several tons and carried to the mountain-top settlements. The later Greeks called these walls cyclopean walls, named after the one-eyed giant race, because the later Greeks felt only giants could move the stones. A walled mountain or hilltop settlement is called a citadel.

Heinrich Schliemann, discoverer of the Mycenaean Civilization

Like the Minoans, the Mycenaeans were a civilization lost to the modern world. No evidence of the Mycenaeans (whom Homer called the Achaeans) or the city of Troy, also talked about in the Iliad, was to be found. However, in the 1800s, a German amateur archaeologist, Heinrich Schliemann, was convinced that the Trojans and Achaeans existed. He was fascinated by the Iliad; with his copy in hand and his wife, Schliemann set out to find ancient Troy. Based on a description in Homer's Iliad, Schliemann found a hill in modern Turkey that fit this description of the location of Troy. Amazingly, as Schliemann dug, ancient Troy was revealed. Feeling he was on a roll, Schliemann went to Greece in 1876, where he uncovered artifacts of the lost civilization of the Mycenaeans at Mycenae, high in the mountains. The Mycenaean palaces proved the wealth of the kings who ruled them. The Palaces included a large meeting hall called a Megaron, and kings were buried in deep shaft graves along with their riches. Later tombs, called tholos or beehive tombs, were built with massive stones and covered with earth.

The major Mycenaean city-states included Mycenae, home of the legendary King Agamemnon from the Iliad; Tiryns, the home of Heracles (Hercules) from Greek mythology; and Pylos, the home of old King Nestor from the Iliad. Pylos, located close to the sea, was the only city-state that did not have cyclopean walls. Therefore, it was not a citadel like Mycenae and Tiryns. Since Greece is mountainous, the best form of transportation is by the sea. The Mycenaeans were seafaring people, and all of the city-states were close to the sea but far enough that, should the city be attacked, the inhabitants would have time to react.

The Mycenaeans were naturally bellicose, attacking others, especially by sea, and fighting among themselves. Though they all spoke Greek and worshipped the same gods, the Mycenaeans were separated into independent city-states, each with its king. The Mycenaeans made weapons and armor from Bronze, giving this age its name: The Bronze Age. The Mycenaeans often settled battles between city-states by one-on-one combat, with each city-state taxiing their champion to battle by chariot.

The Iliad and the Odyssey

The Iliad tells about the attack on the citadel of Troy in Asia Minor by the Achaeans (Greeks). It is very possible that the Mycenaeans were these Greeks. The story tells of Helen, queen of the Mycenaean city-state of Sparta, kidnapped and brought to Troy by the Trojan prince, Paris. The Greek city-states reacted by sending a large fleet to attack Troy to bring Helen back home. Being a citadel, Troy was tough to attack, and the war lingered for ten years. Finally, a Greek and the King of Ithaca, Odysseus, devised a trick by leaving a giant wooden horse behind as the Achaeans pretended to sail away in defeat. The Trojans, thinking the horse was a gift from the defeated Greeks, moved the horse into the city. After a celebration, Odysseus and other Greeks, hiding in the horse, opened the gates for the other Achaeans to enter. The Achaeans razed the city of Troy, and Helen returned to Sparta.

Having picked sides in this conflict, some gods felt that Odysseus had cheated in victory. Odysseus set sail for Ithaca, but a trip that should have taken a few weeks took ten years, as the gods created obstacles in his path. All the while, his faithful wife, Penelope, waited patiently for his return. This part of the story is called the Odyssey, an odyssey, a word now used for any long and challenging journey.

Fall of the Mycenaeans

We have evidence that the Mycenaeans increased the size of the walls around their cities around 1200 BC. Something was threatening the civilization. Perhaps there was increased fighting among the Mycenaean cities or a foreign invasion from the north of Greece. Maybe the long war with Troy took its toll on the civilization. Whatever the reason, the Mycenaean civilization collapsed around 1100 BC. Evidence shows that those who replaced the Mycenaeans burned the grand palace cities.

The Dark Ages (from the fall of the Mycenaeans to the first use of the Greek alphabet)

After the fall of the Mycenaeans, Greece entered a Dark Age. A Dark Age is a time without historical records (writing) and of fear, uncertainty, and violence. Those who replaced the Mycenaeans are called the Dorians. As the story goes, these Greeks from the north were the sons of Heracles (whom the Romans called Hercules). These sons of Heracles had been driven out of the Mycenaean world but vowed to return someday.

The Dorians used iron weapons, and Mycenaean bronze, though more beautiful and artful, was no match for Dorian iron. Iron replaced bronze during the Dark Age. The Dorians did not need the Mycenaean palaces and burned them down.

The Dorians were now the masters of Greece. It was a simpler time and a time without written history. Many Mycenaeans fled from the Dorians across the Aegean Sea to Asia Minor. Surprisingly, one Mycenaean city, Athens, was unaffected by the Dorian invasion. People in Athens carried on many Mycenaean traditions. Meanwhile, in the Middle East, the Phoenicians had developed the world's first alphabet.

The Archaic Period (800-500BC)

The Archaic, or old period of ancient Greece, was thought to have been the beginning of Greek history until the discovery of the Mycenaean Civilization. Although we now know that Greek history dates back to the Mycenaean times, the Archaic Period was a time of rebirth. Between the Mycenaean times and the Archaic Period were the Greek Dark Ages, a time of low population, iron-making, lawlessness, lack of art, and illiteracy (inability to read or write).

To understand the changes in the Archaic Period, we should review the Dark Ages of Greece. Homer gives us our best look into this period in his poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. According to these poems, the Dark Ages was a time when kings had limited power. Kings are described as being poor farmers, thieves, and pirates. An aristocracy ruled during the Dark Ages, men whose families had attained power, but these men were not rich, nor did they have total control over the Mycenaean kings before them. No one person could elevate himself above the rest. Dark Age Greeks could not read or write during this time (illiteracy). A person's loyalty was first to himself and his family, not to his country. Greece was under-populated because there was a limited food supply. The Greeks had no contact with the outside world, like Egypt and Mesopotamia. All of this changed in the Archaic Period.

The Olympic Games

One event during the Archaic Period was the creation of the Olympic Games, traditionally set in 776 BC. Although the Olympics took place in Elis, Greece, in the Peloponnesus, this contest was not a local event. The Olympics was open to all Greek-speaking peoples, wherever they may have come from. The Greeks began to think of themselves as having something in common. At the Olympics, the Greeks were allowed to achieve great things. The Greeks did not believe in a life after death, instead, they felt that immortality was achieved by making a name for yourself, through physical achievements, beauty, and speech. Public adulation was critical, and the Olympic Games, which occurred every four years, gave Greeks this opportunity. Olympic winners were considered heroes and stars in their city-states, and their names lived on for generations.

A New Writing System

Literacy returned during the Archaic Period, not with the Mycenaean Linear B, but with a new writing system, the Greek alphabet. Plato, the Greek philosopher, once said, "The Greeks never invented anything, but what they borrowed, they improved upon." This is true of the alphabet, which the Phoenicians of the Middle East originally invented. In an alphabet, symbols represent sounds; since most languages have about 30 different sounds, it is easy to remember only 30 symbols. Systems like cuneiform and hieroglyphics had hundreds of characters to memorize. Therefore, very few people could read and write with these systems.

The Greeks and the Phoenicians were seafaring people. Like the Mycenaeans, Greeks during the Archaic Period began contacting people outside of the Greek world. When the Greeks saw the Phoenician alphabet, they borrowed most symbols for their sounds. Some Phoenician sounds are not used in Greek, so the Greeks used the Phoenician symbols for those sounds to represent vowel sounds. The Phoenicians did not have symbols for vowels! This improvement made reading ancient Greek easier, and more Greeks became literate.

Colonization, Trade, and Coins

The Greeks began colonizing and settling in areas outside the Greek mainland during the Archaic Period. The first colony outside of the Aegean Sea was at the Bay of Naples in Italy around 750 BC, and the second was at Syracuse on the Island of Sicily. The Greeks began to spread from the Aegean Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. The reason for colonization during this time was an increased population with scarce land in Greece to farm. People took the opportunity to find farmland in distant places.

The Greeks came into contact with Mesopotamia and borrowed from this more advanced area. They also began to trade again with Egypt. The Greeks came into contact with the Lydians of Asia Minor, who were the first to use money in the form of electrum (a combination of gold and silver) coins. The Greeks first used Lydian coins and then created their coinage system.

The Greek historian Herodotus tells an excellent story about King Croesus of Lydia, the wealthiest man in the world. Solon, a wise man from the Greek city-state of Athens, was invited to stay at the palace of King Croesus in Sardis, the capital of his Lydian Empire. Croesus showed Solon a vault packed entirely with gold nuggets and gold dust. After showing Solon his gold, Croesus asks who the most fortunate man Solon had ever known in his travels was. Expecting Solon to answer that Croesus was the most fortunate man, the king was shocked to hear that Tellus of Athens was the most fortunate man Solon had ever known.

What Greeks valued in the Archaic Period

To understand Solon's reply, we must understand the most significant change during the Archaic Period, the rise of the polis or the Greek city-state. The Greek polis included an acropolis (high-city), the old citadel or hilltop fortress from the Dark Ages, and the farmland surrounding it. Unlike the city-states of Mesopotamia, the Greek polis was not only a location but included the men who were the citizens of the polis. Kings ruled mesopotamian city-states, and all of the people living there were subjects to the king, in a Greek polis, citizens had a say in the governing of the city-state and a king was not welcome. This type of government was unheard of in the ancient world until the Greek Archaic Period. Our word politics comes from the word polis. The Greeks in the Archaic period took pride in their polis and placed its well-being ahead of personal or family gain. This was a significant change from the Dark Ages when people looked out for themselves and their families first. In the Archaic Period, no more substantial achievement was to die defending your polis. Now, let's go back to the story of Tellus of Athens.

Solon considered Tellus the most fortunate man he had ever met. Solon told King Croesus that Tellus lived in Athens when his polis was prosperous. Tellus raised two strong sons and lived to see grandchildren. Tellus died in battle while serving his country, and his fellow citizens gave him a public funeral.

Aristocracy and the New Independent Farmer

In the Dark Ages, an aristocracy ruled Greece. Aristocracy means "rule of the best." People were born into the aristocracy, and these families controlled the polis at the early stages of the Archaic Period. Then, farmers outside the aristocracy gradually gained control of family plots of land and some wealth. The farmers could afford armor and, therefore, could help defend the polis in war. Unfortunately, war was common among the Greek poleis (plural for polis). Greece had limited farmland, and the Greek poleis would fight each other for land. Each polis lined up in an infantry formation known as the phalanx, a word that means roller. A phalanx is a large, organized block of men, as many as 200 men wide and eight rows deep. There were not enough men in the old aristocracy to create an immense army, so many soldiers came from the new farmer class.

Tyrants and Tyranny

Now that the farmers were serving as soldiers, they started to demand a say in government. The old aristocracy did what they could to hold on to their power; they were reluctant to give any power to the new farmer class. At some point, a tyrant rose to power. A tyrant was a powerful individual, usually from the aristocracy, who promised change to the new farmer class. Since the farmers outnumbered the aristocracy, it wasn't difficult for a tyrant to seize power. This was an illegal move; the tyrant had no right to seize power. Some Greek tyrants brought about positive changes, including increased wealth for the polis and encouraging the arts, while others selfishly used power for their gain. Tyranny in a Greek polis never lasted more than three generations, and all tyrants were eventually overthrown.

Oligarchy

After a tyrant was overthrown the Greek polis did not go back to the rule of the aristocracy, instead, the new farmer class was given a say in government. This meant that there were many more citizens involved in politics, however, if you consider the many poor who could not afford armour and could not help defend the polis, most people had no say in government. The word used for this form of government is an oligarchy, which means "rule of the few." An oligarchy is based on wealth, not heredity.

Democracy and Athens

In the polis of Athens, an extraordinary change occurred in how people governed it. Athens had always been proud of its Mycenaean heritage, and it was the only Mycenaean city-state that survived the Dorian invasion. In the late Archaic Period, many Athenians were in debt (could pay their lenders). These Athenians could not pay off the debt, and some ended up in slavery. Tyrants rose to power in Athens, but problems persisted. Harsh laws only created more problems; the Athenians were ready for some changes. Solon, the same man who told us of Tellus of Athens, brought the first change. Solon introduced fair laws to Athens, replacing the harsh laws the Athenian named Draco set. Today, we use Draconian to mean any harsh rule of law.

In 510 BC, an Athenian named Cleisthenes introduced a new form of government to Athens. We call it democracy, which comes from two Greek words meaning "the people" and "rule." Every citizen of Athens, rich or poor, was given a voice in government. This form of democracy was revolutionary, though not perfect. To be an Athenian citizen, you had to be twenty years old, and your parents had to be Athenian. Women were not allowed to participate in government. Athenian women led private lives, rarely leaving their homes. Foreigners, criminals, and enslaved people were also excluded. Democracy is based on citizenship, not wealth. Athenian citizens met every ten days in an assembly, and any citizen could speak or make a proposal. Citizens voted for each proposal with black (no) and white (yes) stones. Citizens were also selected by lot (luck) to serve on jury duty. Athenian juries were large; 500 citizens made up an Athenian jury. Once a year, Athenians took a special vote called ostracism, where they would scratch the name of a citizen they would like to have expelled (removed) from Athens on a broken piece of pottery if that name occurred at least 6,000 times; that person was told to leave the city, and he could not return for ten years.

Sparta, a Polis to an extreme

If there was a polis in ancient Greece that valued the state over personal gain or family, it was Sparta. Once a Mycenaean settlement, Sparta was taken over by the Dorian Greeks. As in other city-states in Greece, farmland was scarce. Early in the Archaic Period, the Spartans colonized an area in Southern Italy called Taras, then, between 730 and 710 BC, Sparta attacked neighbouring Messenia. This long, drawn-out war was uncommon in ancient Greece. Most wars lasted two hours. The Spartans forced the defeated Messenians to form a lower class called the helots. The Spartans took the land in Messenia and assigned the helots to the farmland. The Messenians were unhappy with this arrangement, and rebellion was a constant fear to the Spartans.

With the helots farming, all Spartan men became soldiers. This was important because the helots could rebel at any time, sometimes with help from neighboring city-states, like Agros, the enemy of Sparta. When a Spartan boy was born, he was presented to the Council of Elders, 28 men over 60, who acted as a political council in Sparta. The Council inspected the baby, and if it was thought to have any defect, the baby was killed or abandoned in the wild.

Spartan boys lived with their mothers until they were seven when they went to the agoge, a state-run military school. The child was given no shoes, one thin cloak, and barely enough to eat. Older boys at the agoge bullied the new boys. Boys studied music, poetry, gymnastics, and military training at the agoge. The boys also learned moral lessons. Lessons revolved around discipline, self-reliance, and teamwork. Boys graduated from the agoge at age 20 and became teachers for ten years. At age 30, a Spartan man married.

Two kings ruled Sparta, the 28 Council of Elders, who held the position for life, and five ephors, ordinary Spartans elected to this position. The ephors could bring charges against either king and have a king removed from Sparta. Spartan kings led the army. Each king could veto or forbid a decision made by the other king.

The Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars were two wars fought between the Persian Empire and some of the independent Greek city-states. Persia was a mighty empire created by Cyrus the Great. Cyrus conquered one area after another but allowed the conquered people to worship as they pleased, as long as they paid the great king annual tribute and military service.

Greeks living in Persia along the Aegean coast in Asia Minor were called Ionians. The Ionians started a revolt in 499 BC, led by Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus, an Ionian city-state in the Persian Empire. With the help of Athens and Eretria, the Ionians burnt the Persian city of Sardis on the Greek mainland. However, King Darius of Persia reacted and destroyed the Ionian fleet of ships at Lade and burnt the city-state of Miletus in 494 BC; the Ionian Revolt was crushed. Now, Darius turned his eyes on Athens and Eretria and vowed to make them pay for their involvement in this failed rebellion.

Darius' first invasion attempt was from the north. Ahead of his vast army and navy, Darius sent envoys demanding a jar each of earth and water. Those who submitted and agreed to be part of the Persian Empire peacefully were passed by without harm. Refusing to surrender, Athens and Sparta, two Greek city-states, killed the envoys. Darius' invasion was cut short when his navy was shipwrecked off the Mount Athos cape, an area notorious for bad storms. Without the support of the navy, Darius' army was forced to return to Persia. The attack on Athens and Eretria would have to wait for another time.

In 490 BC, Darius began his second invasion attempt. Not as ambitious as the first, Darius sent boats directly across the Aegean Sea, hopping from one island to the next. These boats carried 25,000 infantry and 5,000 horses. The invasion force destroyed the city-state of Eretria and then landed at Marathon, twenty-five miles from Athens.

Along with the Persians traveled Hippias, the last tyrant of Athens, who had been forced to leave the city when Athens became a democracy. Hippias hoped to be restored as a tyrant of Athens, acting on behalf of the king of Persia. Marathon, where the Persians landed, was Hippias' family land. The Athenians marched out to Marathon with a force of 10,000 hoplites. Looking down from the mountain, the Athenian commander, Miltiades, could see that the Persian invaders severely outnumbered him. Miltiades was the perfect commander for this battle since he was once a general in the Persian army. Miltiades sent a day-runner named Pheidippides to Sparta, 140 miles away, to ask for help. The Spartans were observing a religious festival to Apollo and would not march until the next full moon, one week later.

Miltiades decided to attack the Persians. By thinning the middle of his phalanx, Miltiades could widen his army. The Persians were drawn into the weak Athenian middle and surrounded. Around 6,500 Persians died at the Marathon, while the Greeks suffered 192 deaths. The Persians returned home, unable to defeat the Athenians.

Second Persian War

Darius died before he could attack the Athenians again; however, his son, Xerxes, was now king, and he vowed to avenge his father's defeat. In 480 BC, Xerxes led a mighty invasion force from the north, as his father had tried earlier. Xerxes made a floating bridge so his army could cross the Hellespont, the body of water that separates Asia from Europe, then he cut a canal through the Mount Athos peninsula so his ships would avoid the storms that wrecked his father's fleet at the cape.

In August 480 BC, Xerxes army came in contact with a small Greek force led by the Spartan king, Leonidas, in Northern Greece at Thermopylae, a narrow mountain pass. For three days, the Greek force of 10,000 men held back Xerxes' army, possibly 250,000 soldiers. On the third day, the Persians found a small mountain path and came around the other side of the defenders. Leonidas and the other Spartans lost their lives at Thermopylae; nothing was in the way of Xerxes' army and the city of Athens.

Thebes, a city-state north of Athens, joins Persia against fellow Greeks, including its long-time enemy, Athens.

Panic set in at Athens, the Athenians sent a messenger to the Oracle of Delphi at the temple of Apollo to ask her for advice. The Oracle said everything was lost except for the one behind the wood walls. Since Athens had walls of stone, many were confused by this message. An Athenian named Themistocles was sure of this message. Earlier Athens had discovered a silver mine, and Themistocles convinced the Athenians to build warships with its newfound wealth. 200 ships were ready just in time for Xerxes' invasion. Themistocles told the Athenians that the "wall of wood" was the warships.

The Athenian population was evacuated to the nearby island of Salamis. When Xerxes entered the city of Athens, he killed anyone who stayed behind, carried off the riches of the city, and razed Athens. Xerxes was successful where his father, Darius, had failed.

Now there was the question of the Greek fleet in Salamis Bay; should Xerxes advance with his larger navy and attack the Greek fleet? If Xerxes could defeat the Greeks on the sea, all of Greece would be his, including Sparta. All of Xerxes' advisors suggested a sea battle, except for the one woman commander, Queen Artemisia of Halicarnassus, an Ionian Greek, fighting on the side of the Persians. Artemisia sent five warships from her homeland in support of the Great King. Artemisia suggested that Xerxes was already the master of Athens, and cautioned him that the Greeks were superior to his navy in these waters. Xerxes ignored her advice and launched an attack.

The Battle of Salamis (September 480 BC)

The Battle of Salamis took place in the Bay of Salamis. Here the out-numbered Greek navy of 380 warships destroyed about half of the Persian navy. The Battle of Salamis was a turning point in history; without the navy to support the army, Xerxes could not advance further into Greece.

Taking Queen Artemesia's advice, Xerxes returned home to Persia with half of his army. Xerxes' brother-in-law, Mardonius, remained in Greece with the other half of the Persian army to do whatever damage he could, but Persia would not take over Greece.

Battles of Plataea and Mycale (479 BC)

The Persians suffered a double defeat when on the same day in 479 BC, they lost a land battle in Greece at Plataea and had their fleet burned in Asia Minor at Mycale by the attacking Greek navy. At Plataea, the largest battle of the war, 100,000 Persians were defeated by 40,000 Greeks, including Athenian and Spartan hoplites. Mardonius lost his life on the battlefield, what remained of the Persian army limped home.

The Persian Wars gave the Greeks a new feeling of confidence. The Ionian Greek cities, once subject states to the Persian king, gained their independence. The Greek world would go on to achieve great things, led by the city-state of Athens.

Greece – The Classical Period (500-336 BC)

From the Persian Wars to the conquests of Philip II of Macedonia

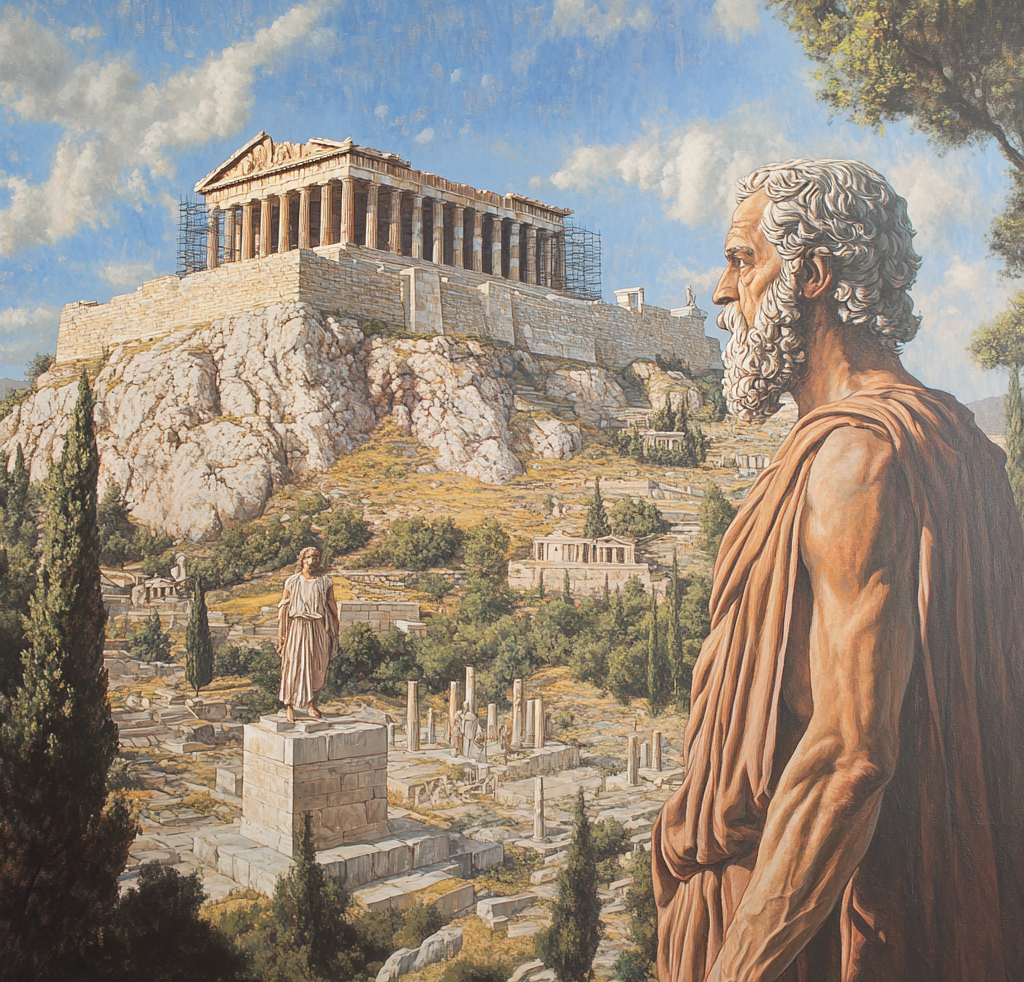

The Classical Period of ancient Greece was a time when the Greeks achieved new heights in art, architecture, theatre, and philosophy. Democracy in Athens was refined under the leadership of Pericles. The Classical Period began with the Greek victory over the Persians and a new feeling of self-confidence in the Greek world. This was a war for freedom, and the Greeks would continue on, free from Persian rule. The Persian Wars was one of the rare times that several Greek city-states cooperated for the sake of all Greek people. Not since the Trojan War, 800 years earlier, had the Greeks joined together. Greece would go on to great achievements, especially Athens. One of the most spectacular achievements in Athens during this time was the rebuilding of the Parthenon, a temple dedicated to Athena on the Acropolis.

When we talk about the accomplishments of the Greeks in the Classical Period, we are really talking about Athens. The polis of Athens prospered after the defeat of the Persians in 479 BC. As you read in the last chapter, Athens had a fleet of over 200 warships. This large fleet, a result of the Persian Wars, was something new to the Greek world. No polis had ever possessed a navy as large as the Athenian navy. It was the Athenians who contributed most of the Greek warships at the Battle of Salamis.

The Delian League

The Ionian city-states gained their independence after the Persian Wars, however, the threat of a Persian attack was real. The Persian Empire was as large, powerful, and rich as it always had been. Greek city-states in and around the Aegean Sea needed protection, and Athens was the logical protector, with its large navy. Athens also depended on trade routes throughout the Aegean Sea and into the Black Sea for grain to feed its large population. Many Greek city-states in the Aegean islands and Asia Minor joined with Athens to form an alliance in 478-77 BC called the Delian League. The allies, around 150 Greek cities, met on the Island of Delos, the supposed birthplace of Apollo. Athens was made the leader of the league. Each member had to pay money to a common treasury, which was held in a bank on the island of Delos or contribute ships and crew to the league navy. The alliance was intended to keep the Greek allies free from Persian rule and make Persia pay for the damages they caused during the Persian Wars. In 466 BC at the Battle of Eurymedon, off the south coast of Asia Minor, the Athenian navy, led by Cimon, destroyed the Persian fleet. It was now clear that Athens ruled the Aegean Sea. No power, including the Persians, could now challenge Athens' navy.

In 480, Xerxes and the Persian army razed the city of Athens, the temple on top of the Acropolis was robbed and destroyed. After the Persian Wars, the Athenians set out to rebuild their city, including surrounding the city with stone walls. Some of the neighbouring Greeks were uncomfortable with the idea of the Athenians building walls, they were concerned that these walls, along with the large Athenian navy, would cause the Athenians to become aggressive. Sparta was one of the concerned city-states. Themistocles went to Sparta and told the Spartans that, yes, the Athenians were building walls, and it was none of Sparta's business. Themistocles warned Sparta to stay out of Athens' business, and that Athens would not interfere with Sparta. This was the beginning of distrust between the two city-states that had fought together during the Persian Wars. Sparta, hesitant to get involved in affairs outside of the Peloponnesus, did not join the Delian League.

Surprisingly, Themistocles, the man who convinced the Athenians to build a navy with their silver, was not rewarded. In a democracy, there was no room for standout personalities like Themistocles, and he was ostracized. Themistocles was forced to leave Athens for ten years. He never returned, and instead went to Persia, where he lived out the rest of his life.

In the 460s BC, an earthquake hit Sparta, some Spartans were killed, so the helots, the Spartan slaves, took this opportunity to revolt. Desperate, Sparta asked Athens for help. The Athenian named Cimon led an Athenian army to help Sparta, but when they arrived the Spartans had second thoughts and sent Cimon and the Athenian army back home. Perhaps the Spartans feared the spreading of democratic ideas by these Athenians, as Sparta was not fond of this new way of governing. The Athenians were insulted, and Cimon, on the advice of an Athenian named Pericles, was ostracized.

445-429 BC: The Age of Pericles

Pericles came from a famous family, his father was a hero at the Battle of Mycale, and his uncle was Cleisthenes, the father of democracy. So, it is no surprise that Pericles was a believer in democracy. Pericles became a politician in Athens. His first public office was choregos, a person who funds and produces plays. Pericles funded the plays of Aeschylus, one of the famous playwrights of Athens, including his play, Persians in 472 BC. Persians was a play about the Persian Wars and the Greek victory.

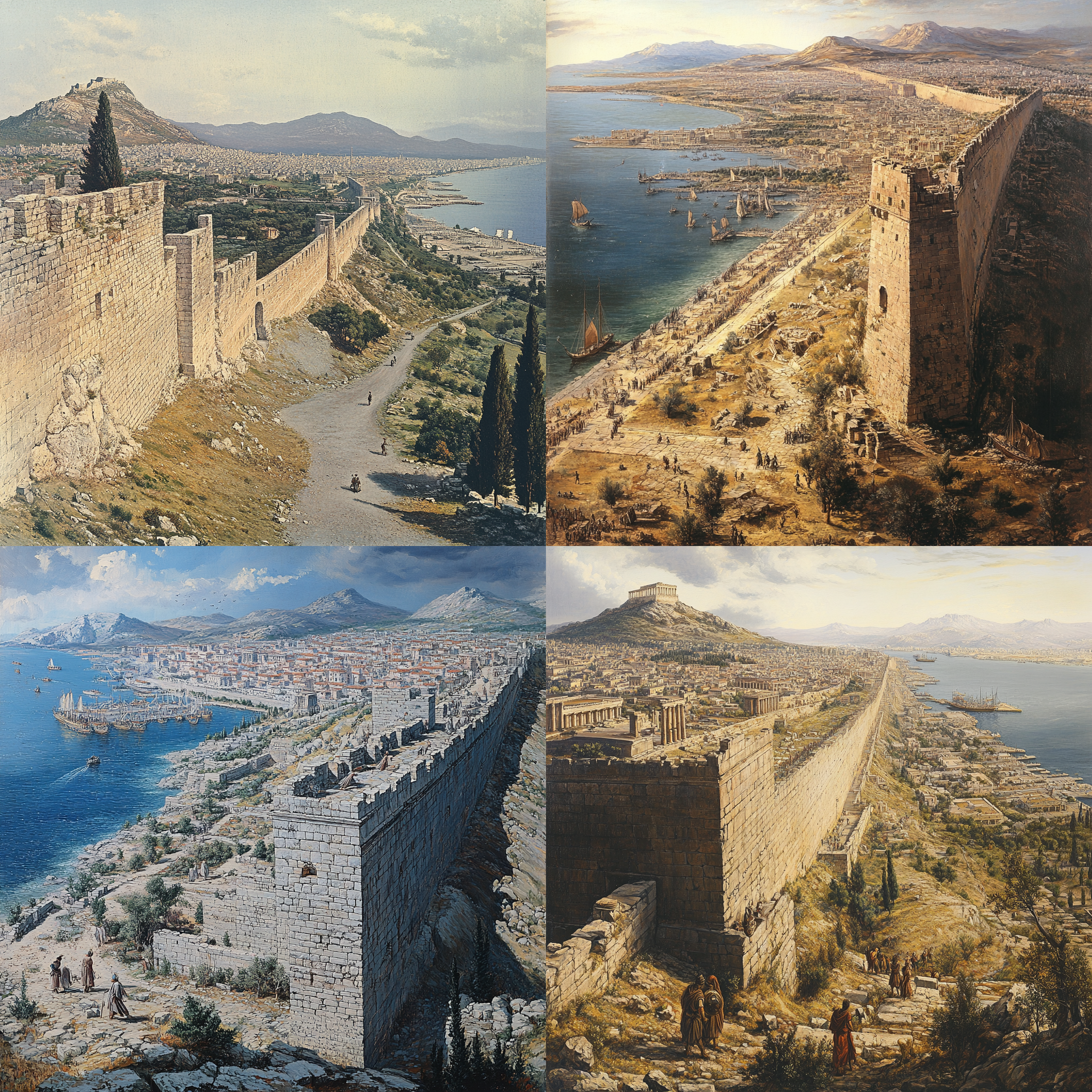

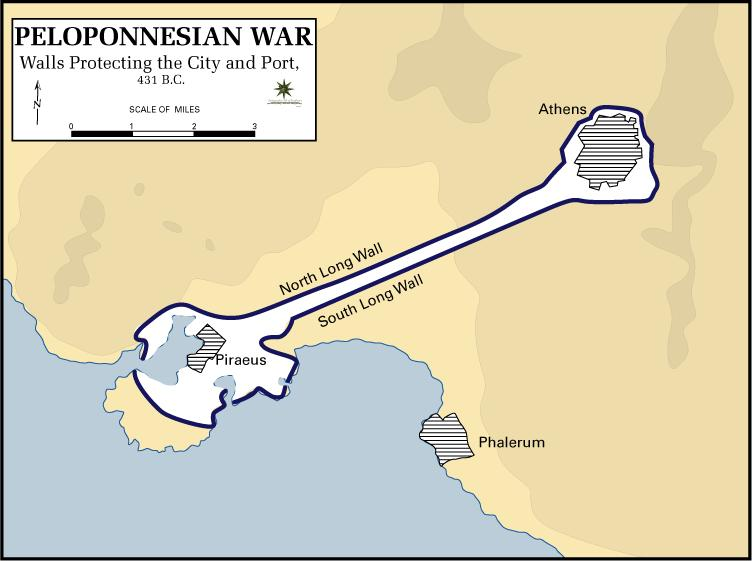

Pericles is best known for holding the office of archon, or general. Pericles was first elected to this one-year position in 458 BC, he was re-elected 29 times. As archon, Pericles had the Long Walls built between Athens and the nearby port city of Piraeus. Piraeus was about five miles from Athens and had three harbours, which were a perfect location for the Athenian navy base.

Pericles planned the rebuilding of the destroyed Acropolis. Pheidias, a friend of Pericles, created a new statue of Athena, sculpted in ivory and gold, on the Acropolis. The Parthenon, a temple that housed the Athena statue, was built to replace the temple destroyed by the Persians. Pericles used Delian League treasury money for this building project. Some historians claim that Pericles was a builder on a scale with Ramses the Great of Egypt.

Pericles made changes to Athenian democracy. At the beginning of the democracy, public positions were filled by the rich. This was because there was no pay for government jobs. Since the poor could not afford to stop working for any long period of time, they could not serve in these jobs. Pericles wanted to make sure all citizens had a chance to fill government jobs, he made these jobs paying positions, so even the poor could serve in the Athenian government. Pericles also granted free admission to the poor who could not afford to go to the theatre, these seats were paid for by the government. Pericles made the law that a man's mother and father had to be Athenian for him to be a citizen of Athens.

It was during the Classical Period that Herodotus and Thucydides wrote their history books. Theatre flourished as Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles wrote tragedies, while Aristophanes wrote comedies. Hippocrates lived during this period and is given credit as one of the first doctors. Pythagoras, the famous mathematician, lived into the Classical Period. Socrates considered the father of philosophy, gathered followers on the streets of Athens during the Classical Period.

Everything was going well for the Greeks until the outbreak of the Peloponnesian Wars, between Athens and Sparta. We will learn more about these wars and their effect on the Greek world in the next chapter.

The Peloponnesian Wars ("The Great War" 431-404 BC)

The Peloponnesian Wars were a series of conflicts between Athens and Sparta. These wars also involved most of the Greek world, because both Athens and Sparta had leagues, or alliances, which brought their allies into the wars as well. The Athenian Thucydides is the primary source of the wars, as he fought on the side of Athens. Thucydides was ostracized after the Spartans' decisive victory at the Battle of Amphipolis in 422 BC, where Thucydides was one of the Athenian commanders. Thucydides wrote a book called The History of the Peloponnesian War. From 431 to 404 BC the conflict escalated into what is known as the "Great War." To the Greeks, the "Great War" was a world war, not only involving much of the Greek world, but also the Macedonians, Persians, and Sicilians.

The Peloponnesian Wars were ugly, with both sides committing atrocities. Before the Peloponnesian Wars, wars lasted only a few hours, and the losing side was treated with dignity. The losers were rarely if ever, chased down and stabbed in the back. Prisoners were treated with respect and released. Thucydides warns us in his histories that the long wars go, the more violent, and less civilized they become. During the Peloponnesian Wars, prisoners were hunted down, tortured, thrown into pits to die of thirst and starvation, and cast into the waters to drown at sea. Innocent school children were murdered, and whole cities were destroyed. These wars turned very personal, as both Athens and Sparta felt that their way of life was being threatened by the other power.

As you read in the last chapter, Athens, along with about 150 other city-states, formed the Delian League as a way to protect against a possible Persian invasion. If any one of the Delian league members was attacked, the other league members would come to their support. In 466 BC, an important battle took place at Eurymedon, off the coast of Asia Minor. The Delian League navy crushed the Persian navy so badly, that some of the Delian league members thought the threat by Persia was gone, and the league was no longer necessary. Some of the islands in the Aegean wanted to leave the league, they no longer wanted to pay money and provide ships. Athens stepped in and did not permit these Greeks to leave the league. Athens treated these city-states harshly by tearing down their walls, taking their fleet of ships, and insisting they continue to pay the league taxes. Apparently is was easy to join the Delian League, but impossible to back out, and the league was beginning to look more like an Athenian empire.

The Pentecontaetia “the period of fifty years” (a word created by Thucydides) was the time from the end of the Persian Wars to the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides tells us that this was a time of distrust between Athens and Sparta. Thucydides tells us that Athens's greatness during this period brought fear to Sparta. What is interesting about that statement is that for the first time in history, emotion is said to be the cause of war.

Let me give you one example of the distrust between the two city-states. As you read in the last chapter, a great earthquake rocked Sparta in 465 BC. The desperate Spartans asked Athens for help, but when the Athenians sent hoplites to Sparta, the Spartans, having second thoughts, sent them back to Athens. The Spartans put down the helot rebellion on their own, but could not remove a band of helots from high on a mountain top fortress. A deal was struck where the Spartans promised the helots they could leave the citadel peacefully if the helots promised to move outside of the Spartan territory. Thinking that the helots would scatter, the Spartans were alarmed to find out that the Athenians allowed all of these helots to settle in Naupactus, an Athenian-controlled harbour city on the Corinthian gulf, directly across from Peloponnese. Here, the helots were free to do great harm to Sparta and her allies by controlling the gulf.

Athens had everything going for it before the outbreak of the "Great War." Athens controlled the Aegean Sea, and bullied the Delian League so that only two other city-states in the league had their own navies. In 454-53 BC, Athens moved the Delian League treasury from Delos to Athens, creating a bank in the back of the newly-built Parthenon on the Acropolis. Athens then demanded 1/60th of the league money for a "donation to Athena," which really meant it was a tax on the league members going directly to Athens. The Athenians had allies all around them by land, including an alliance with Megara, a former Peloponnesian League friend of Sparta. Athens also and controlled the seas.

Phase One of the Great War - The Archidamian War (431-421 BC)

The Peloponnesian League met in 432 BC. Corinth, a city-state in that league, complained that Sparta was not doing enough to control Athens. Sparta decided to go to war with Athens. Pericles, whom we read about in the last chapter, was the clear leader of Athens at this point, replacing Cimon, who had been ostracized, and later, after returning to Athens, had died fighting the Persians. Pericles was confident in a quick Athenian victory. If the Spartans and their allies should invade Athenian territory, the Athenians could hide behind the Long Walls. Pericles knew that the Spartans had no knowledge of siege warfare, or destroying walls. The Spartans could destroy the farmland of Attica (Athenian territory), but grain would continue to flow from the Black Sea to the port of Piraeus, and then into Athens.

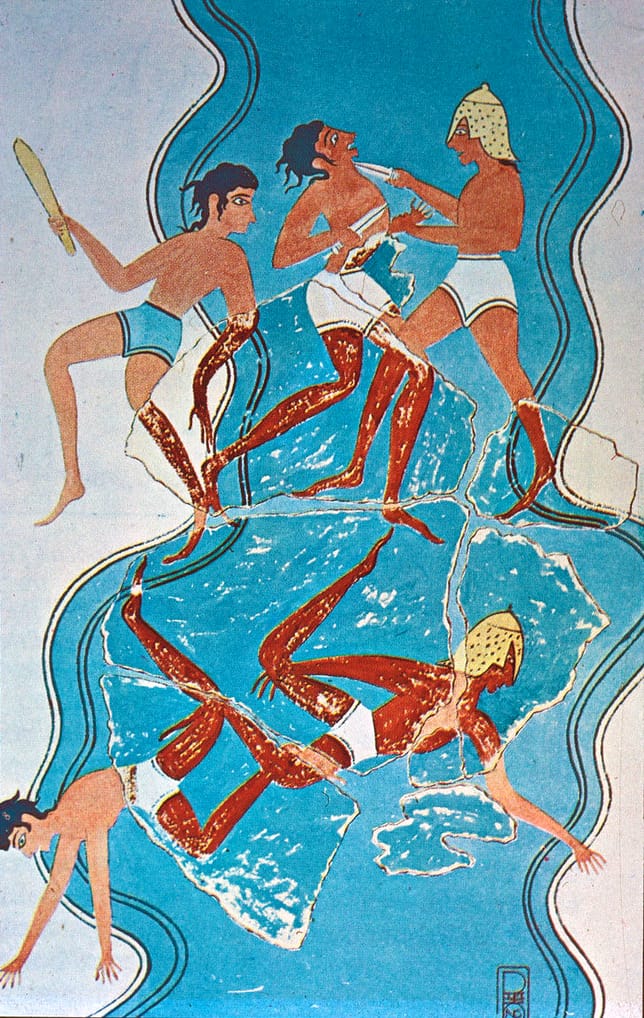

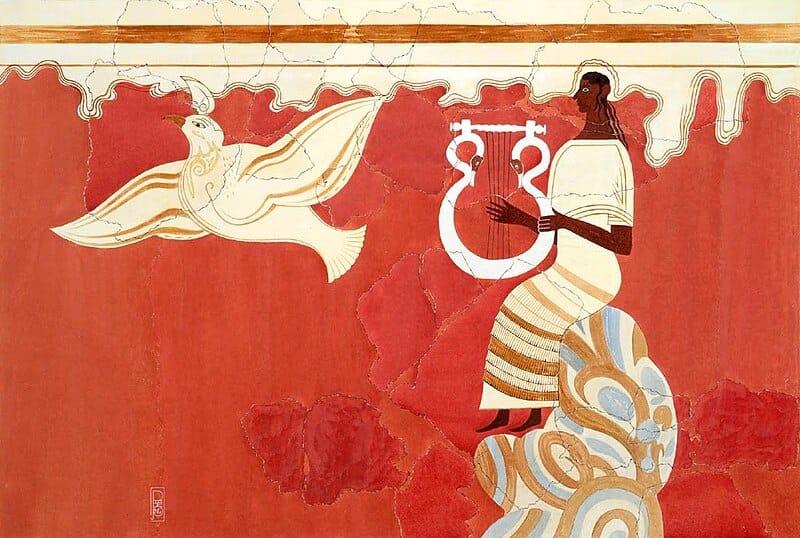

(image 1 - left) Two helmeted warriors and a chariot on a fresco from Pylos dated LH IIIA/B (about 1350 BC) circa 1350. | (image 2 - center) Scene Fresco from Nestor's palace in Pylos dated LH IIIB (about 1300 BC). Watercolor reconstruction by Piet de Jong. Archaeological Museum of Chora, Messinia, Greece.| (image 3 - right) Lyre Player and Bird Fresco from the Throne Room of Nestor's palace in Pylos dated LH IIIB (about 1300 BC). Watercolor reconstruction by Piet de Jong. Archaeological Museum of Chora, Messinia, Greece. circa 1300

In 431 BC, King Archidamius of Sparta invaded Athenian territory. The Spartans only stayed for a few months, cut down some olive trees, and then headed back to the Peloponnese. They repeated this in 430 BC. In that same year, Pericles gave his famous "Funeral Oration," in which he praised the dead Athenian soldiers for giving their lives for Athens. Pericles went on to say that Athens would win because Athens' way of life was clearly better than Sparta's.

Pericles felt Athens would win a quick victory over Sparta. Pericles felt that after a few years of raiding the Athenian countryside, the Spartans would eventually become frustrated by the Long Walls and agree to peace on Athens' terms. But then, something went terribly wrong for Athens. In 429 BC, a plague hit Athens. Some of the grain coming into Piraeus was tainted, and people started to die in the streets. Athens had become over-crowded as all of the people of Attica were now cramped into the city, fearful of the Spartans. Disease spread quickly, and the Long Walls became a prison, rather than a fortress. Around 30,000 Athenians died, including Pericles, the Athenian leader. Thucydides contracted the plague but survived. The Spartans quickly left Attica, fearful that they may catch the plague as well. The war dragged on.

In 428 BC the Athenians had gained a foothold in the Peloponnese, by taking the old City of Pylos. When the Spartans tried to regain the city, 400 Spartan hoplites became trapped on the nearby Island of Sphacteria. The Athenians starved the Spartans into eventual surrender and brought 120 Spartan hoplites back to Athens. They placed these Spartan hoplites on display in a human zoo, as no Athenian had seen a Spartan hoplite up close. Sparta was desperate to have these warriors returned, and was willing to come to terms with Athens.

Phase Two – Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition (421-413 BC)

In 421 BC, a 50-year peace treaty was signed by Sparta and Athens, the treaty was called the Peace of Nicias, named after the Athenian who made the treaty. One of the terms was that the captured Spartan hoplites be allowed to return home. It was a shaky peace at best, and in 420 BC, the Spartans were accused of marching hoplites into Elis during an Olympic year. Sparta was not allowed to compete in the Olympic Games. At this time some of the Peloponnesian League cities decided to rebel against Sparta and were helped by Argos, the long-time enemy of Sparta, and by Athens. In 418 BC, the largest land battle of the war took place in the Peloponnese at Mantinea. Here Sparta defeated Argos, Athens and their Peloponnesian allies, and returned them to the Peloponnesian League. During the war, Athens always won at sea but lost on land. Some historians compare Athens to the whale, and Sparta to the elephant.

416-413 BC – The Sicilian Expedition. The Island of Sicily was 800 miles to the west of Athens.

In 416 BC, Alcibiades, a young Athenian and follower of the philosopher, Socrates, convinced the Athenians to take the war to Sicily, by attacking the city-state of Syracuse. Syracuse was a colony of Corinth and friendly to the Peloponnesian League. Alcibiades was very convincing, as he was an excellent public speaker. Alcibiades made the point that if Athens should take Syracuse, all of Sicily would fall, and give Athens new riches and power. It would only be a matter of time before Sparta would surrender. Sicily was 800 miles away from Athens, and it would take several ships in the Athenian navy to attack Syracuse.

The night before the expedition set sail, the sacred statues of Hermes were vandalized. Alcibiades and his friends were accused of drinking and then smashing the statues. This was awkward because Alcibiades was the leader of the expedition. Alcibiades was allowed to set sail with the Athenian fleet, but when the fleet arrived at Thurii, a Greek colony on the southern coast of Italy, a messenger ship from Athens caught up with the fleet. This small boat was to take Alcibiades back to Athens, as he had been tried and convicted of smashing the statues. Unwilling to return, Alcibiades, along with his pet dog, jumped ship and swam to Thurii.

Nicias was now in charge of the attack on Syracuse, even though he had argued against it back in Athens. When the Athenian fleet landed in Sicily, close to Syracuse, the unwilling Nicias dragged his feet. The Athenians were slow to make the necessary walls to close off Syracuse by land, even though the mighty Athenian Fleet had closed of Syracuse by the sea.

Meanwhile, Alcibiades fled to Sparta, where he convinced the Spartans to help the Syracusans. Sparta sent one boat to Syracuse with a commander by the name of Gylippus. Gylippus raised an army in Sicily and defeated the Athenians. Foolishly, Nicias asked Athens to send reinforcements. When the new soldiers arrived, the Athenians finally decided the war was lost and to head back home. A rare lunar eclipse prevented the Athenian fleet from leaving the harbour, and during that delay, the Syracusans placed a metal chain across the harbour, trapping the Athenian fleet. The Athenians fled by land but were hunted down, killed or thrown into pits to starve. Oddly, the Syracusans admired the tragedies of the Athenian playwright, Euripides, and any Athenian prisoner who could give a good performance of lines of Euripides was released. Nicias was killed, and the Athenians lost most of their fleet. This was the turning point of the war.

Peloponnesian War Phase Three: The Ionian War (412-404 BC)

At the advice of Alcibiades, the Spartans built a permanent fort in Attica so they could destroy the Athenian countryside year-round. This also cut off access to the silver mine, and the Athenians were running out of resources. Alcibiades was flirting with the queen of Sparta while her husband was in Athenian territory, as Alcibiades had suggested, year-round. When the Spartan king found out about this, he returned to Sparta, only to find that Alcibiades had fled again, this time to Persia.

Now living in the Persian Empire, Alcibiades convinced the satrap of Lydia to slow down payments to Sparta, which the Persians had used to help Sparta gain a fleet of warships. Alcibiades was now no friend to Sparta, and he told the Persian satrap that by keeping Athens and Sparta even in power, they would eventually wear each other out, leaving the way clear for the Persians to gain power.

Seeing the influence Alcibiades had with Persia, Athens made it clear they wished for him to return and become a general. Athens was hopeful Alcibiades could convince the Persians to give aid to Athens. The Delian League was beginning to crumble, and Athens needed new allies. Alcibiades eventually returned to Athens to a hero's welcome. The charges brought up against Alcibiades for smashing the statues were dropped.

Alcibiades had great victories at the sea battles of Abydos and Cyzicus, keeping Athens in control of the Hellespont, but in 406 BC, at the Battle of Notium, Alcibiades was defeated by Lysander, a Spartan who was comfortable at sea. This Spartan whale would go on to become famous, while Alcibiades was recalled to Athens. Rather than face a trial, Alcibiades retired.

In 406 BC, the Athenians won the Battle of Arginusea, but the commanders of the fleet did not attempt to rescue sailors from the sea. Back in Athens these commanders were put on trial and sentenced to death. Socrates, the father of philosophy, protested this outcome. Socrates was no fan of democracy, as he felt it led to mob rule and poor decision-making.

Finally, in 405 BC, at the Battle of Aegospotami, Lysander captured the Athenian fleet in the Hellespont. Lysander then sailed to Athens and closed off the Port of Piraeus. Athens was forced to surrender, and Sparta won the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC.

Spartans' terms were lenient. First, the democracy was replaced by an oligarchy of thirty Athenians, friendly to Sparta. The Delian League was shut down, and Athens was reduced to a limit of ten triremes. Finally, the Long Walls were taken down. Within four years, the Athenians overthrew the "Thirty Tyrants" and restored their democracy. Looking for someone to blame for the loss to Sparta, the Athenians placed Socrates on trial. He was found guilty of corrupting the minds of young Athenians, and not believing in the gods. Socrates was sentenced to death by hemlock, a slow-acting poison that you drink from a cup.

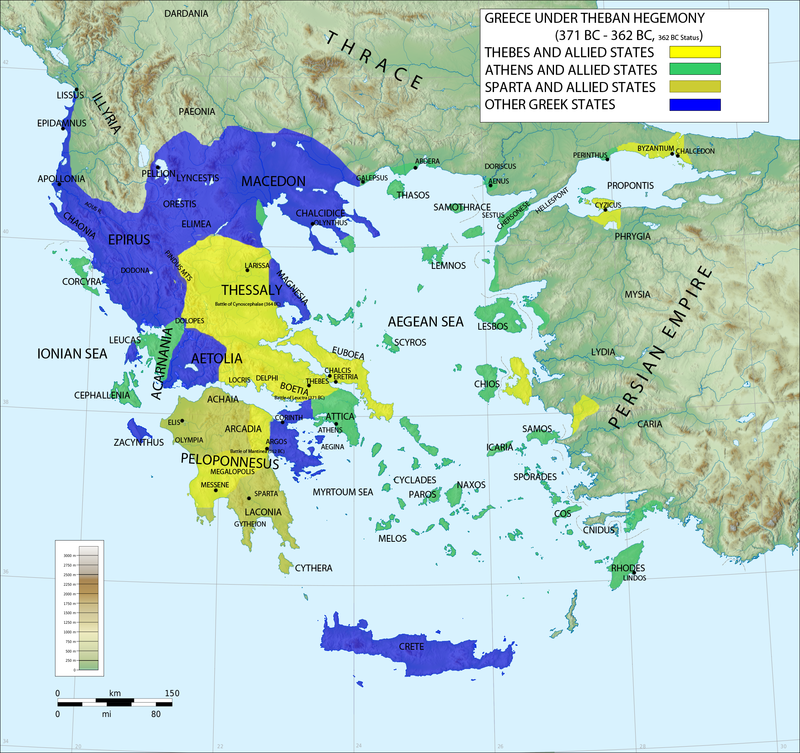

The Peloponnesian War had a lasting effect on the Greek world. Both Sparta and Athens were weakened. Thebes, defeated Sparta at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC to become the most powerful Greek polis, and then, Philip II of Macedonia defeated Thebes and the Greek allies to become master of the Greek world. We will learn more about Philip and his son Alexander in the next section.

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age

The Hellenistic Age 336-30 BC (from Alexander’s crowning to the death of Cleopatra)

The word Hellenistic comes from the root word Hellas, which was the ancient Greek word for Greece. The Hellenic Age was the time when greek culture was pure and unaffected by other cultures. The Hellenistic Age was a time when Greeks came in contact with outside people and their Hellenic, classic culture blended with cultures from Asia and Africa to create a blended culture. One man, Alexander, King of Macedonia, a Greek speaker, is responsible for this blending of cultures.

To understand how the Kingdom of Macedonia dominated the Greek world, we need to first take a look at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC, between Sparta and Thebes. As you read in the last chapter, Sparta defeated Athens in 404 BC, ending the Peloponnesian War. Though Sparta was victorious, it was also weakened by this war. Thebes, an ally of Sparta during the Peloponnesian War, became powerful after the conflict. Sparta and Thebes went to war over territory close to Thebes. The battle took place in Boeotia, near the city-state of Leuctra in July 371 BC.

Epaminondas, the Theban general, introduced a new fighting technique at Leuctra. As you remember, the Greeks fought in a phalanx, a solid block of men. The best men would form on the right side, or weak side, as a place of honour. The Spartan phalanx at Leuctra was twelve men deep. In the traditional formation, the best soldiers of one army would always face the weakest of the other. Epaminondas placed his best soldiers on the left, guaranteeing that they would face the best Spartans. He also took no chances, forming his left side 50-men deep. Epaminondas held the Theban right-side back, refusing to fight the Spartan left. The Theban left of 50-men deep pushed the Spartan right, trampling men and killing the Spartan king. Sparta was not used to losing battles. Sparta would go on, but this was the end of Sparta as the dominant Greek city-state and the end of its control over most of the Peloponnese.

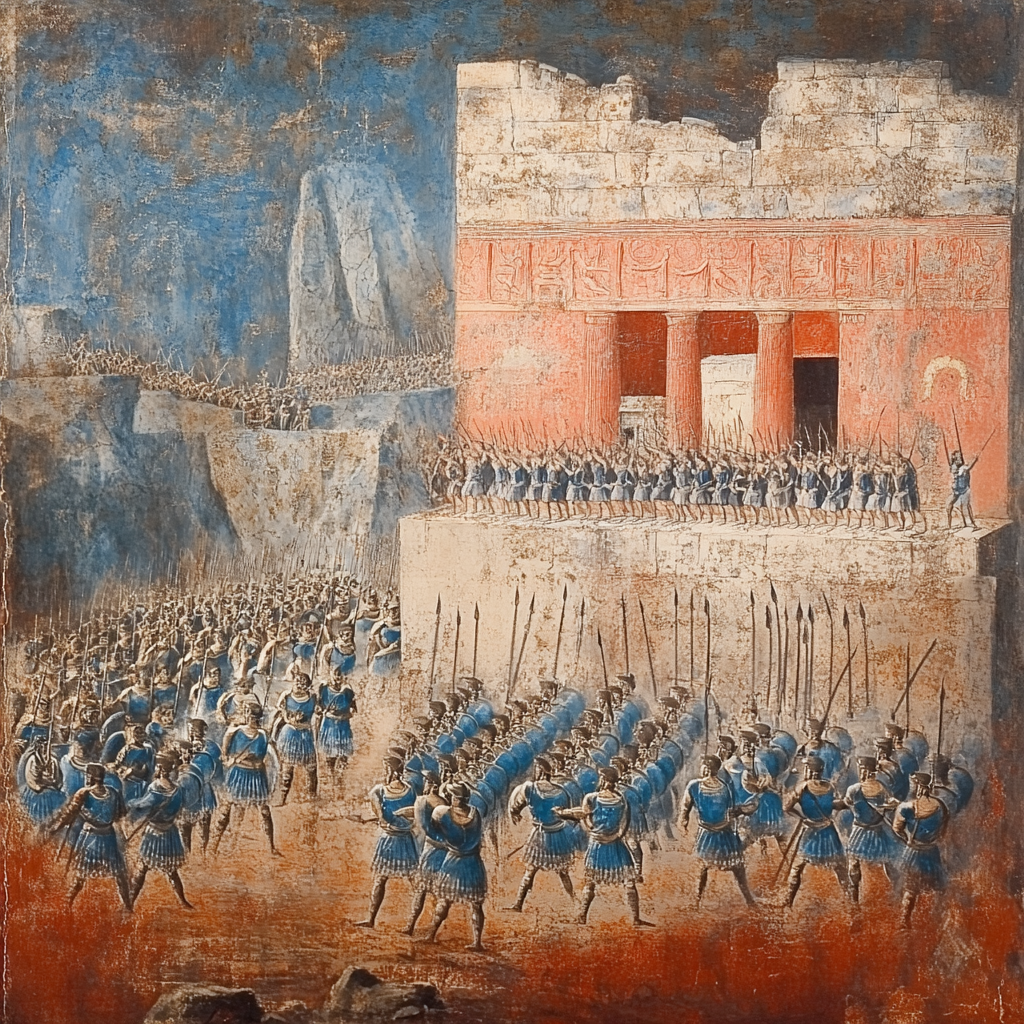

The Battle of Leuctra in Boeotia, Greece, just north of Athens. 1) The larger Spartan army in blue tries to out-flank the Theban right side. 2) Spartan cavalry is chased off the battlefield by the Theban cavalry. 3) The Theban's right side includes peltasts, javelin throwers, which harass the Spartan left side. 4) The Theban left side includes a super phalanx 50-rows deep, which bears down on the Spartan right. 5) The Theban super phalanx, including the Theban "Sacred Band" of three hundred men, rolls over the Spartan right, killing the Spartan king. seed 2205843689 -- seed 2205843689

Watching the Battle of Leuctra and learning Theban tactics was a young man from Macedonia name Philip. Philip was a hostage in Thebes, as Thebes controlled Macedonia at this time. Philip returned to Macedonia in 365 BC. Six years later, in 359 BC, Philip became King of Macedonia. As king, Philip used both diplomacy and war to expand Macedonian territory. Philip married into the families of the surrounding kingdoms and captured a gold mine, which provided Macedonia with wealth. Philip is given credit for creating the sarrisa, a long pike used in the Macedonian phalanx.

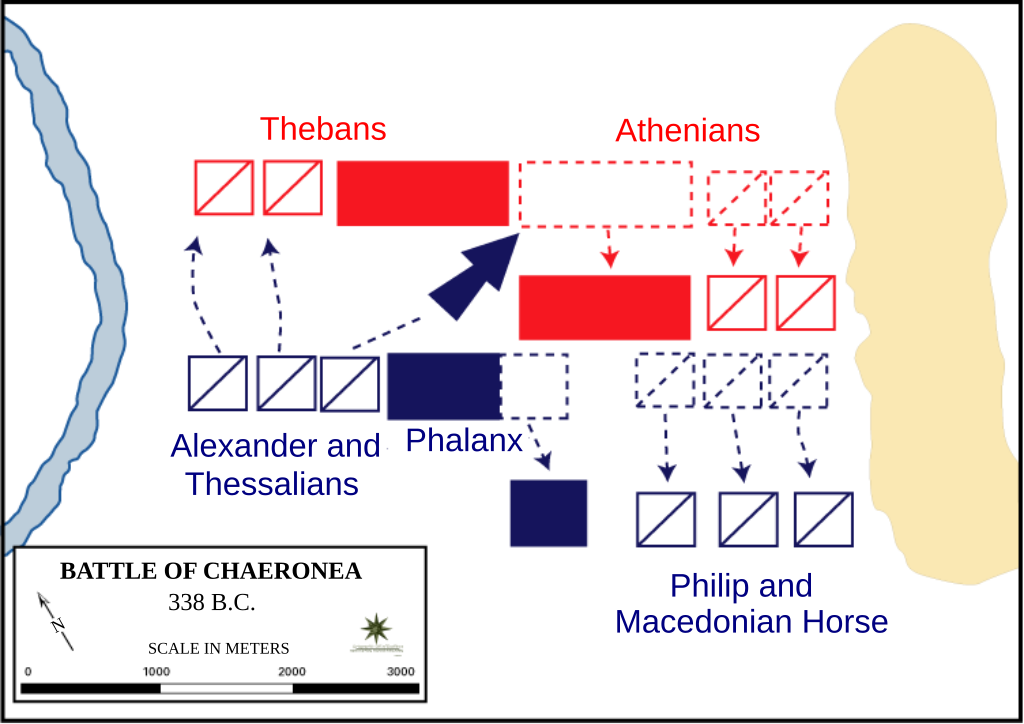

In 338 BC, at the Battle of Chaeronea, King Philip II of Macedonia used similar tactics to those that he witnessed at the Battle of Leuctra to defeat a Theban and Athenian army sent to meet him. Philip was now clearly the master of the Greek-speaking world. He created the Corinthian League of Greek allies. These allies vowed not to fight each other, and to provide troops for Philip's planned invasion of the Persian Empire.

Philip's plan of conquest was cut short when, in 336 BC, at his daughter's wedding, he was assassinated by one of his own bodyguards. Many people believe the assassin did not act alone, and that Olympias, Philip's fourth wife, was behind the plot to murder the king. The crown of Macedonia was passed to Alexander, Philip's son by Olympias. Alexander was only twenty years old when he became king but had fought at Chaeronea two years before, leading the left-wing of his father's cavalry.

In 335 BC, in the first year of his reign, Alexander was challenged by a rebellion in Thebes. Thebes resisted as Alexander's army advanced to the city. Alexander made an example of Thebes by totally destroying the city except for the temples and the home of Pindar, one of his favourite poets.

After destroying Thebes, Alexander moved on to Corinth, where he established himself as the new leader of the Corinthian League. Alexander pardoned those city-states that had rebelled against him. Like his father, Alexander wanted to conquer the Persian Empire with the help of the Greeks. While in Corinth, Alexander sought out his favourite philosopher, Diogenes. Diogenes lived in the streets of Corinth in a barrel. When Alexander found the old man, he asked Diogenes if there was anything he could do for him. Diogenes replied, "Yes, you can stand a bit to the side, you are blocking my sunlight." When Alexander's bodyguards laughed at the old man, Alexander quieted them by saying, "If I were not Alexander, I would be Diogenes!"

In 334 BC, Alexander crossed the Hellespont with his Macedonian and Greek army and into the Persian Empire. His first stop was the ruins of the City of Troy. The Iliad and Odyssey were Alexander's favourite books, and it was said that he always carried a copy of them wherever he went. It was natural then, that he would want to visit the legendary city. It was at Troy that Alexander pulled the shield of Achilles from off the wall of a small museum amid the ruins. He would use the 900-year old shield in all of his battles. Alexander learned to appreciate the Iliad and nature from his teacher Aristotle, a Macedonian who studied in Athens at Plato's Academy.

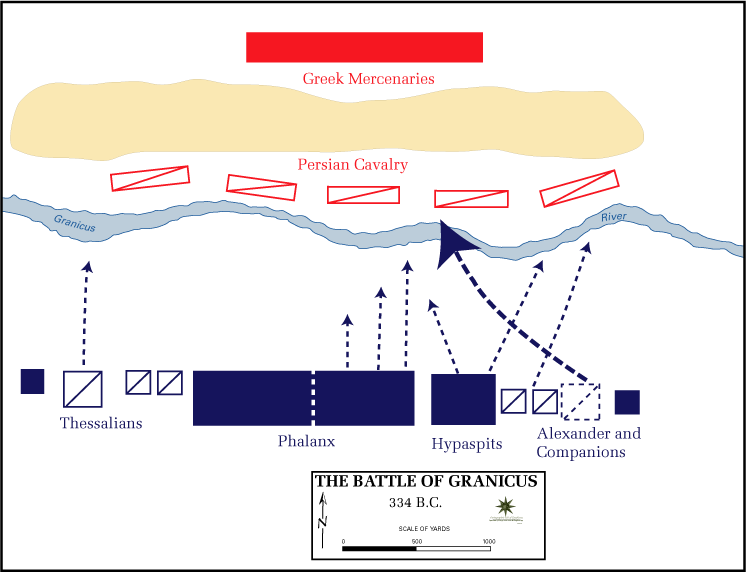

At Granicus River, Alexander met the first resistance to his invasion as he was blocked by a Persian army. The King of Persia at this time was Darius III. Darius was not overly concerned about the young Macedonian king and was not present at this battle. Though he was almost killed, Alexander rallied his army and defeated the Persians. Darius blamed the victory on his general, he would be sure to be with his army at the next battle.

After the Battle of Granicus River, Alexander travelled along the coast, making sure these city-states were now on his side. Alexander could not afford to go deep into the Persian Empire with enemies at his back. Next, Alexander marched inland to the city of Gordion, the location of the famous Gordian Knot. It was said that anyone who could remove the oxcart from the temple, by untying the knot, would be the king of the world. Alexander could not resist this challenge. The knot was tied so the ends could not be found. Crying out, "It doesn't matter how it's done!" Alexander took a swing with this sword, broke the rope, and pulled the oxcart away from the temple.

In 333 BC, Alexander met a large Persian army led by the Great King, Darius III at Issus. Darius had blamed the loss at Granicus River on the fact that he was not there; this time he would lead his army against the young Macedonian king. Alexander always led from the front of his army, he was the first to meet the enemy, which gave his army much courage. Darius, on the other hand, led from behind, on his chariot, surrounded by bodyguards. Although this may seem cowardly compared to Alexander, it was the safe thing to do. The king, being at the battle, gave the Persians courage, but he was safe from harm. Although the Persian's outnumbered Alexander's army, the battle location was between the sea and a mountain range, and the Great King could not out-flank Alexander's smaller army. Alexander won the battle by moving around the Persian army and charging on his horse with his Companion Cavalry straight for Darius. Darius fled the scene, leaving his mother, wife, and two daughters behind. Alexander captured the royal family and treated them with kindness and respect. Darius's mother became one of Alexander's most trusted advisors and was at his bedside when he died in Babylon.

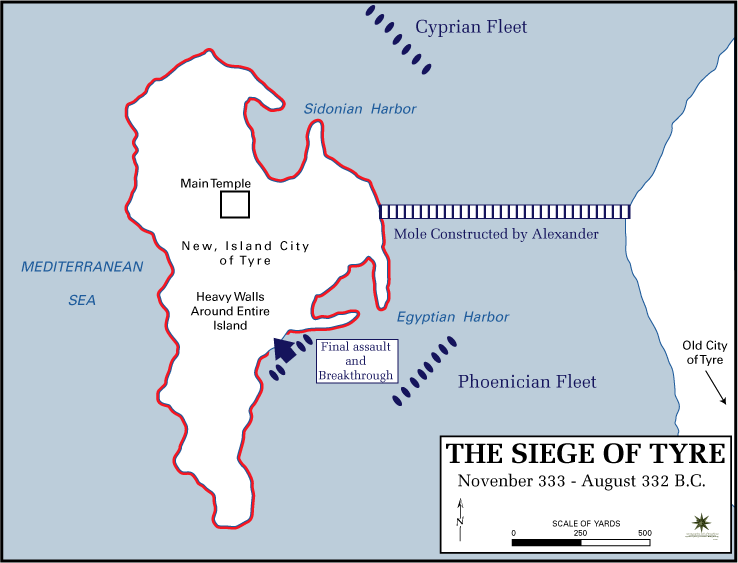

In 332 BC, Alexander reached the city-state of Tyre in Phoenicia, now part of the Persian Empire. Tyre was important to King Darius because it was the navy base for his fleet of triremes. Alexander needed to control this fleet if he wished to go further into the Persian Empire. Alexander asked the Tyrians to hand over their fleet to him, but they refused. Tyre was on an island about a quarter-mile off the shore and had massive defensive walls. The Assyrians and Babylonians had previously attempted a siege of Tyre and had failed. Alexander built two land bridges in an attempt to connect Tyre to the mainland. Next, he attacked the Persian fleet with ships of his own. It took seven months, but Alexander finally took Tyre. He could now advance into Persia without a threat to his supply lines.

In 331 BC, Alexander and his army entered Egypt. The Egyptians, always unhappy with their Persian rulers, handed the city of Memphis over to Alexander. Alexander was proclaimed pharaoh and wore the double crown. Alexander, with a few of his friends, travelled through the Egyptian desert to the Oasis of Siwa. Here Alexander visited the temple of Ammon-Zeus. Alexander asked the oracle at Siwa a question. Alexander was always closer to his mother. His father was always off to war and showed very little emotion toward his son. Alexander's mother, named Olympias, was from the Kingdom of Epirus. When Olympias separated from Philip, she brought young Alexander back to her homeland. It was in Epirus that Olympias told her son that Zeus, the king of the gods was his father and not Philip. Alexander asked the oracle if this was true, and the oracle seemed to reply that he was indeed the son of Zeus. When Alexander returned from the desert, he made plans for a new port city in Egypt which he called Alexandria, after himself. Alexander left Egypt behind and headed into the heart of the Persian Empire, determined to defeat Darius again.

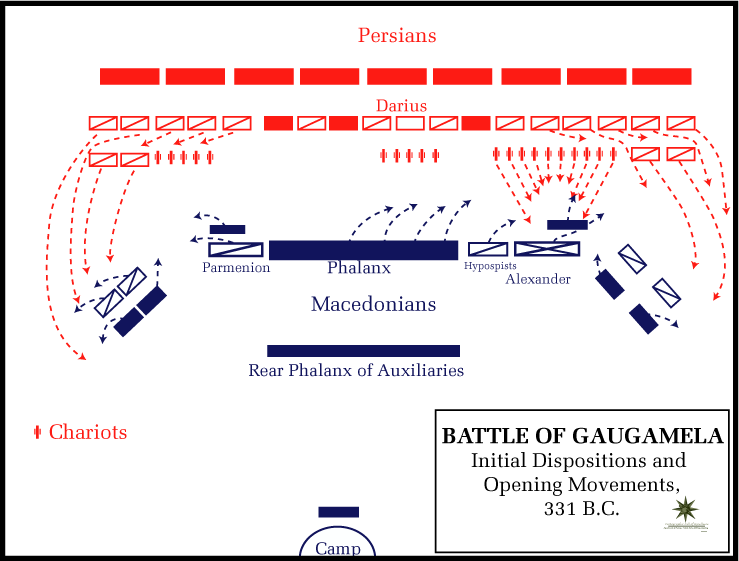

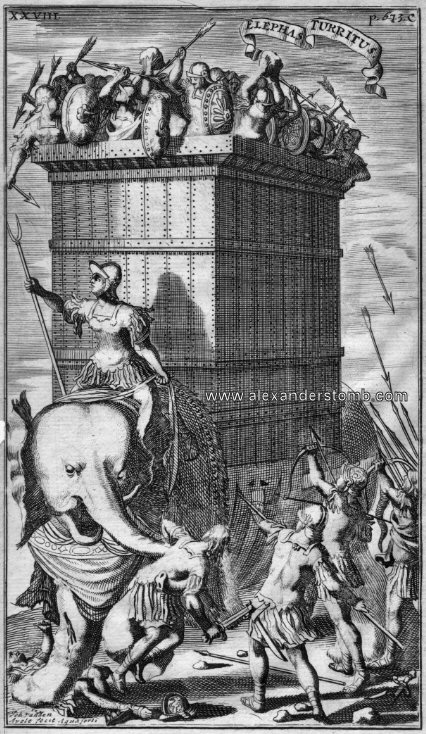

In the same year that Alexander left Egypt, he moved deep into the Persian Empire; and at a place called Gaugamela (camel's back), a large battle took place in 331 BC. King Darius was taking no chances at this battle. Darius assembled an army twice as large as Alexander's. Darius also seemed to have an answer for the Macedonian phalanx and sarrisa. Darius brought war elephants to the battlefield, along with scythed chariots. Elephants are used in warlike tanks, they trample everything in their path, this was also the first time Greeks had seen these beasts, and Alexander's army was in awe of the elephants. The scythed chariots could cut into and break up the phalanx. However, both of these elements proved disappointing. The elephants fell asleep during the battle and were captured by Alexander. Alexander's men simply moved to the side and let the scythed chariots pass through the lines. Alexander won the Battle of Gaugamela, and Darius, for the second time fled the battlefield. Whereat Granicus, Darius could blame the fact that he wasn't there for failure, and at Issus, he could blame the narrow battlefield, he had no excuse at Gaugamela.

After the defeat of Darius at Gaugamela, there was nothing to stop Alexander's army from marching to Persepolis, the capital of the Persian Empire. Alexander was now clearly the King of Persia, not Darius. Alexander spent many days in Persepolis, rather than pursuing Darius. One night, in 330 BC, the city was set on fire. It is unclear whether Alexander authorized this destruction, but what is clear is that he did not move to stop it.

Alexander moved on and tracked Darius down. When he caught up with Darius, Alexander found him wounded and dying; Darius had been attacked by his own subjects. Darius died as Alexander gave him his last drink of water. Darius thanked Alexander for treating his family kindly and said, "Who would have thought, that with all the people in the world, I should receive a last act of kindness from you."

Alexander moved on into what is now the country of Afghanistan, where he had his most difficult time defeating the people in this area. Afghanistan is mountainous and, as we've seen many times in history, impossible to control. Alexander was the first to learn this lesson. Alexander did create an alliance with one group of people in this area by marrying Roxanne, and the local princess. Battle.

From Afghanistan, Alexander turned east with his army. In 326 BC, in what is now the country of India, Alexander encountered his most difficult opponent, Porus, a local ruler. Porus had 200 war elephants as part of his army. Porus prevented Alexander's army from crossing the Hydaspes River. Alexander used trickery to cross the Hydaspes, and, in a hard-fought battle, in which Alexander lost several men, defeated Porus. Alexander was so impressed by Porus, that he allowed him to continue as the local ruler of the region. Alexander acquired some war elephants and riders from Porus.

After the Battle of Hydaspes River, with a friend in Porus to the west, Alexander wished to continue east to China on his quest of total world domination, however, after the hard-fought victory against Porus, his troops had had enough. Many soldiers hadn't seen their families for ten years and wanted to return to Greece and Macedonia. Alexander's army refused to follow the king any farther east. After retreating to his tent to sulk for two days, Alexander emerged saying that the gods willed that he should return home.

Alexander's army made the difficult march south in what is now Pakistan. Many obstacles and people unfriendly to Alexander fought him along the way. During a siege of a city, Alexander was almost killed. When Alexander reached the coast at Pattala, he used ships to bring many of the original soldiers of his army back to Greece and Macedonia, the others he marched back through a desert. There was little water, and many of his soldiers died during this desert crossing. Alexander survived the crossing, making it back to Babylon, the capital of his empire. In 323 BC, while in Babylon, Alexander got very sick with a fever and died. He had no plans for a successor to his empire, and his infant son was too young to rule. As his generals gathered around their dying king, they asked him whom he would leave his empire to, Alexander replied, "To the strongest!"

Alexander's generals took his advice and began to fight against each other, each general trying to carve out a large portion of the empire for himself. This period was known as the Wars of the Diadochi (Successors). The first battle was over Alexander's body. While his coffin was returning to Macedonia, the body was hijacked by Ptolemy, one of the Diadochi, and brought to Alexandria, in Egypt, where it remained for years on display. In 301 BC, the Battle of Ipsus, in Asia Minor, involving most of the Diadochi, saw one of the successors, Antigonus, killed. Ipsus proved that no single ruler would control the entire empire, as the others would form alliances to defeat the strongest. It was during these wars that Greek armies learned how to use war elephants, turning these ancient tanks against each other. The riders of the elephants were always from India, as the Greek-speakers could not control the beasts.

Alexander's Legacy

Alexander spread Greek culture throughout the Persian Empire, including parts of Asia and Africa. Alexander respected the local cultures he conquered and allowed their customs to continue. Alexander himself embraced local customs, wearing Persian clothes and marrying Persian women. Alexander encouraged his soldiers to marry Persian women, in this way, the children of these marriages would share both Persian and Greek cultures.

Alexander created the Hellenistic Age, a time when Greek culture mixed with the various cultures of Alexander's Empire. This was a time of advances in learning, math, art, and architecture. Some of the great names of learning in this Age include Archimedes, Hero, and Euclid. It was a time of relative peace, after the Wars of the Diadochi (322-275 BC).

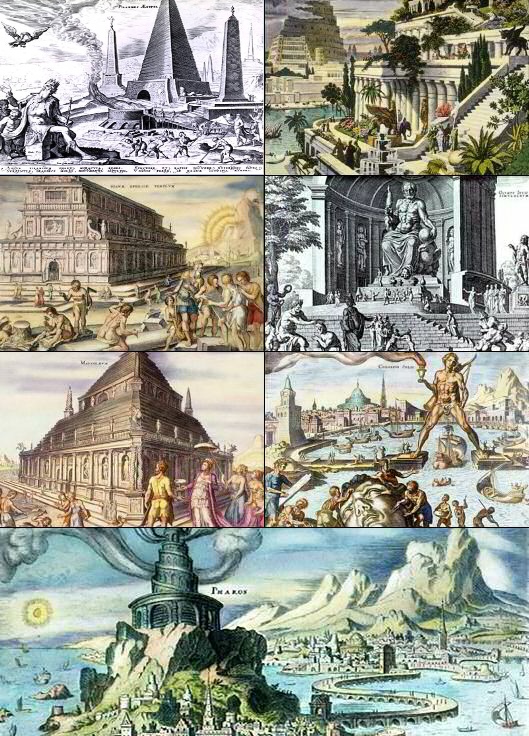

Because of the relative peace during the Hellenistic Age, travel and trade increased. Antipater of the city of Sidon created a poem around 140 BC that listed seven wonders of the world. Antipater picked these buildings and statues for their art and architecture. The list became a set of tourist attractions for people of the ancient world.

The great cities of the Hellenistic Age included Antioch in Syria, Pergamum in Asia Minor, and Alexandria in Egypt, with its Library of Alexandria, the largest library of the ancient world. Although none of these cities were in Greece, they all had Greek architecture.

Art in the Hellenistic Age was very different from the Greek art of the Hellenic Age. Earlier Hellenic art was idealistic and perfect. Hellenic statues resembled Greek gods, however, in the Hellenistic Age, the art looked realistic, the way people really are, including their flaws.