ANALYTIC PHILOSOPHY: prior to 1950, the tradition of late 19th century and early 20th century Anglo-European philosophy presents and defines itself as essentially distinct from and opposed to all forms of idealistic philosophy, especially Immanuel Kant’s transcendental idealism[1] and 19th century neo-Kantian philosophy, and G.W.F. Hegel’s absolute idealism and late 19th century British neo-Hegelian philosophy;[2] philosophy carried out by means of the methods of logical or linguistic analysis; philosophy committed to the thesis that there exists one and only one kind of necessary truth: logical truths or analytic truths; philosophy principally concerned with formulating and knowing logical or analytic truths; philosophy that mirrors and valorizes the formal sciences (especially logic and mathematics) and the natural sciences (especially physics); after 1950, the tradition of mid- to late-20th century and early 21st century Anglo-American philosophy that presents itself as essentially distinct from and opposed to “Continental” philosophy.[3]

Controversy: see the entry on “Continental philosophy.”

ELABORATION

The 140-year tradition of Analytic philosophy has two importantly distinct phases: classical Analytic philosophy (from roughly 1880 to 1950), and post-classical Analytic philosophy (from roughly 1950 to the present).

Classical Analytic philosophy began in the 1880s with the work of Gottlob Frege (especially his Foundations of Arithmetic, and his logical and semantic writings, especially his Concept-Script [Begriffsschrift] and “On Sense and Meaning [or Reference]” [Über Sinn und Bedeutung]), and then got fully underway in late 19th and early 20th century with the work of G.E. Moore (especially his essays “The Nature of Judgment” and “The Refutation of Idealism” and his book Principia Ethica) and Bertrand Russell (especially his co-authored book with A.N. Whitehead, Principia Mathematica, and his essay “On Denoting”).

In 1921, Russell’s research student and subsequently his collaborator, Ludwig Wittgenstein, published the most important book in classical Analytic philosophy, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which heavily influenced the Logical Empiricist, aka Logical Positivist, doctrines of the Vienna Circle, whose most important members or fellow-travellers included Rudolf Carnap, Moritz Schlick, Otto Neurath, Frank Ramsey, A.J. Ayer, Kurt Gödel, Alfred Tarski, and W.V.O. Quine.

During the period from 1900-1940, classical neo-Kantian philosophy in Germany and France, and British neo-Hegelian philosophy (carrying over somewhat into the USA—see, for example, T.S. Eliot’s Harvard PhD dissertation on F.H. Bradley, and the philosophy of Josiah Royce more generally[4]), both came to a more or less bitter end.

Slamming the door behind the idealists, and triumphantly (indeed, even triumphalistically) replacing them, and just as often also taking up their vacated university positions, a group of Young Turk avant-garde philosophers carrying the banner of the new tradition of classical Analytic philosophy came onto the scene, following on from Frege but led by Moore, Russell, the young Wittgenstein, the Vienna Circle Logical Empiricists/ Positivists (especially Carnap), and Quine.

Classical Analytic philosophy also stands in an important elective affinity with the rise of what James C. Scott calls high modernism, especially in the applied and fine arts and the formal and natural sciences.[5]

At the same time, the classical Analytic philosophers were engaged in a serious intellectual competition with phenomenology, especially Husserlian transcendental phenomenology[6] and Heideggerian existential phenomenology.[7]

Simultaneously, however, there was also an emerging organicist movement in philosophy, including Henri Bergson’s Matter and Memory in 1896, Creative Evolution in 1907, Samuel Alexander’s Space, Time, and Deity in 1920, John Dewey’s Experience and Nature in 1925, and especially A.N. Whitehead’s “philosophy of organism” in Process and Reality in 1929.

By the end of World War II, the early Cold War, and the period of the sociopolitical triumph of advanced capitalism and technocracy in the USA, classical Analytic philosophy had triumphed in a social-institutional sense; organicist philosophy had virtually disappeared except in a vestigial form, as an aspect of American pragmatism; and existential phenomenology and all other kinds of non-Analytic philosophy, under the convenient and pejorative catch-all label, “Continental Philosophy,” gradually became the social-institutional Other and slave of Analytic philosophy.[8]

By 1950, Quine’s devastating critique of the analytic-synthetic distinction in “Truth by Convention,” “Two Dogmas of Empiricism,” “Carnap and Logical Truth,” and Word and Object effectively ended the research program of classical Analytic philosophy and initiated post-classical Analytic philosophy.

In the early-to mid-1950s, post-classical Analytic philosophy produced a Wittgenstein-inspired language-driven alternative to Logical Empiricism/Positivism, ordinary language philosophy.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, powered by the work of H. P. Grice and Peter Strawson, ordinary language philosophy became conceptual analysis.[9]

In turn, during that same period, Strawson created a new “connective”—that is, holistic—version of conceptual analysis, that also constituted a descriptive metaphysics.[10]

In the 1970s, 1980s, and early 1990s, Strawson’s connective version of conceptual analysis gradually fused with Donald Davidson’s non-reductive naturalism about language, mind, and action (sometimes rather misleadingly called semantics of natural language), John Rawls’s holistic method of “reflective equilibrium,” and Noam Chomsky’s psycholinguistic appeals to intuitions-as-evidence, and ultimately became what can be called The Standard Model of mainstream post-classical Analytic philosophical methodology, by the end of the 20th century.[11]

In the late 1990s and first two decades of the 21st century, a domestic critical reaction to The Standard Model, combining direct reference theory, scientific essentialism and modal metaphysics,[12] yielded recent and contemporary Analytic metaphysics.[13]

In contemporary mainstream post-classical Analytic philosophy, co-existing and cohabiting with The Standard Model and Analytic metaphysics, is also the classical Lockean idea that philosophy should be an “underlaborer” for the natural sciences, especially as this idea was developed in the second half of the 20th century by Quine and Wilfrid Sellars, and their students, as the materialist or physicalist (whether eliminativist, reductive, or non-reductive) and scientistic doctrine of scientific naturalism, and again in the first three decades of the 21st century, in even more sophisticated versions, as experimental philosophy, aka “X-Phi,” and the doctrine of second philosophy.[14]

More precisely, scientific naturalism includes four basic theses: (i) anti-mentalism and anti-supernaturalism, which says that we should reject any sort of explanatory appeal to non-physical or non-spatiotemporal entities or causal powers, (ii) scientism,[15] which says that the formal sciences (especially logic and mathematics) and the natural sciences (especially physics) are the paradigms of knowledge, reasoning, and rationality, as regards their content and their methodology alike, (iii) materialist or physicalist metaphysics, which says that all facts in the world, including all mental facts and social facts, are either reducible to (whether identical to or “logically supervenient” on) or else strictly dependent on, according to natural laws (aka “naturally supervenient” or “nomologically supervenient” on) fundamental physical facts, which in turn are naturally mechanistic, microphysical facts, and (iv) radical empiricist epistemology, which says that all knowledge and truths are a posteriori.

So, to summarize, scientific naturalism holds first, that the nature of knowledge and reality are ultimately disclosed by pure logic, pure mathematics, fundamental physics, and whatever other reducible natural sciences there actually are or may turn out to be, second, that this is the only way of disclosing the ultimate nature of knowledge and reality, and third, that even if everything in the world, including ourselves and all things human (including language, mind, and action), cannot be strictly eliminated in favor of or reduced to fundamental physical facts, nevertheless everything in the world, including ourselves and all things human, is metaphysically grounded on and causally determined by fundamental physical facts.

Generalizing now, the central topics, or obsessions, of the classical Analytic tradition prior to 1950 were meaning and necessity, with special emphases on (i) pure logic as the universal and necessary essence of thought, (ii) language as the basic means of expressing thoughts and describing the world, (iii) the sense (Sinn) vs. Meaning, aka reference (Bedeutung) distinction, (iv) the conceptual truth vs. factual truth distinction, (v) the necessary truth vs. contingent truth distinction, (vi) the a priori truth vs. a posteriori truth distinction, and (vii) the analytic vs. synthetic distinction.

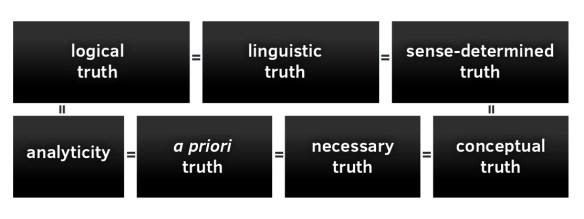

Correspondingly, a common and profoundly embedded thread running through all of these sub-themes is the following rough-and-ready multiple identity (or at least necessary equivalence):[16]

So, a very useful way of characterizing classical Analytic philosophy from late 19th century Frege to mid-20th-century Quine, is to say that it consisted essentially in the rise and fall of the concept of analyticity.

By vivid contrast to classical Analytic philosophy, however, the central commitment, and indeed dogmatic obsession, of post-classical Analytic philosophy since 1950 until today at 6am, continues to be scientific naturalism, which in turn is grounded in the mechanistic worldview.

See, e.g., R. Hanna, Kant and the Foundations of Analytic Philosophy (Oxford: Clarendon/Oxford Univ. Press, 2001). ↩︎

See, e.g., P. Hylton, Russell, Idealism, and the Emergence of Analytic Philosophy (Oxford: Clarendon/Oxford Univ. Press, 1990). ↩︎

See R. Hanna, The Fate of Analysis: Analytic Philosophy From Frege to The Ash-Heap of History, and Toward a Radical Kantian Philosophy of The Future (New York: Mad Duck Coalition, forthcoming in 2021). ↩︎

See, e.g., B. Kuklick, The Rise of American Philosophy (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 1977). ↩︎

See J.C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Conditions Have Failed (New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press, 1999); A. Janik and S. Toulmin, Wittgenstein’s Vienna (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1973); The Vienna Circle, “The Scientific Conception of the World,” in S. Sarkar (ed.), The Emergence of Logical Empiricism: From 1900 to the Vienna Circle (New York: Garland Publishing, 1996), pp. 321–340, also available online at URL = http://www.manchesterism.com/the-scientific-conception-of-the-world-the-vienna-circle/; P. Galison, “Aufbau/Bauhaus: Logical Positivism and Architectural Modernism,” Critical Inquiry 16 (1990): 709-752; G. Reisch, How the Cold War Transformed Philosophy of Science: To the Icy Slopes of Logic (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005); and J. Isaac, “Donald Davidson and the Analytic Revolution in American Philosophy, 1940-1970,” Historical Journal 56 (2013): 757-779. ↩︎

See, e.g., R. Hanna, “Transcendental Idealism, Phenomenology, and the Metaphysics of Intentionality,” in K. Ameriks and N. Boyle (eds.), The Impact of Idealism (4 vols., Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013), vol. I, pp. 191-224. ↩︎

See, e.g., R. Hanna, “Kant in the Twentieth Century,” in D. Moran (ed.), Routledge Companion to Twentieth-Century Philosophy (London: Routledge, 2008), pp. 149-203, at pp. 149-150. ↩︎

See, e.g., R. Rorty, “Philosophy in America Today,” in R. Rorty, Consequences of Pragmatism (Minneapolis, MN: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1982), pp. 211-230; J. McCumber, Time in the Ditch: American Philosophy and the McCarthy Era (Evanston, IL: Northwestern Univ. Press, 2001); T. Akehurst, “The Nazi Tradition: The Analytic Critique of Continental Philosophy in Mid-Century Britain,” History of European Ideas 34 (2008): 548-557; T. Akehurst, The Cultural Politics of Analytic Philosophy: Britishness and the Spectre of Europe (London: Bloomsbury, 2011); A. Vrahimis, “Modernism and the Vienna Circle’s Critique of Heidegger,” Critical Quarterly 54 (2012): 61-83; A. Vrahimis, “Legacies of German Idealism: From The Great War to the Analytic/Continental Divide,” Parrhesia 24 (2015): 83-106; J. McCumber, The Philosophy Scare (Chicago IL: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2016); S. Bloor, “The Divide Between Philosophy and Enthusiasm: The Effect of the World Wars on British Attitudes Towards Continental Philosophies,” in M. Sharpe et al. (eds.), 100 Years of European Philosophy Since the Great War (Cham, CH: Springer, 2017), pp. 201-213; J. Katzav and K. Vaesen, “On the Emergence of American Analytic Philosophy,” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 25 (2017): 772-798; J. Katzav, “Analytic Philosophy, 1925-1969: Emergence, Management and Nature,” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 26 (2018): 1197-1221; and A. Vrahimis, “Russell Reads Bergson,” in M. Sinclair and Y. Wolf (eds.), The Bergsonian Mind (London: Routledge, forthcoming), also available online at URL = https://www.academia.edu/41702088/Russell_Reads_Bergson. ↩︎

See, e.g., R. Hanna, “Conceptual Analysis,” in Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 10 vols., ed. E. Craig (London: Routledge, 1998), vol. 2, pp. 518-522, available online at URL = https://www.academia.edu/11279103/Conceptual_Analysis. ↩︎

See P.F. Strawson, Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics (London: Methuen, 1959); and P.F. Strawson, Analysis and Metaphysics: An Introduction to Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1992). ↩︎

See, e.g., F. Jackson, From Metaphysics to Ethics: A Defense of Conceptual Analysis (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1998). ↩︎

See, e.g., R. Hanna, “A Kantian Critique of Scientific Essentialism,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58 (1998): 497-528; R. Hanna, “Why Gold is Necessarily a Yellow Metal,” Kantian Review 4 (2000): 1-47; R. Hanna, Kant, Science, and Human Nature (Oxford: Clarendon/Oxford Univ. Press, 2006), chs. 3-4; and R. Hanna, Cognition, Content, and the A Priori: A Study in the Philosophy of Mind and Knowledge (THE RATIONAL HUMAN CONDITION, vol. 5) (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2015), section 4.5. ↩︎

The leading figures of Analytic metaphysics include David Lewis, David Chalmers, Kit Fine, John Hawthorne, Theodore Sider, and Timothy Williamson; and some of its canonical texts are Lewis’s On the Plurality of Worlds (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), Sider’s Writing the Book of the World (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2011), Chalmers’s Constructing the World (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2012), and Williamson’s Modal Logic as Metaphysics (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2013). ↩︎

See, e.g., W.V.O. Quine, “Epistemology Naturalized,” in W.V.O. Quine, Ontological Relativity and Other Essays (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1969), pp. 69-90; W. Sellars, Science, Perception, and Reality (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1963); J. Knobe and S. Nichols (eds.), Experimental Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2008); and P. Maddy, Second Philosophy: A Naturalistic Method (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2007). ↩︎

On the crucial distinction between science and scientism, see R. Hanna, THE END OF MECHANISM: An Apocalyptic Philosophy of Science (Unpublished MS, 2021), available online at URL = https://planksip.me/2Ult4rB; and also S. Haack, Science and its Discontents (Rounded Globe, 2017), available online at URL = https://roundedglobe.com/books/038f7053-e376-4fc3-87c5-096de820966d/Scientism and its Discontents/. ↩︎

I’m grateful to Otto Paans for creating and sharing this diagram. ↩︎

If you feel so inclined, please feel free to show your support for Robert via his Patron page (https://www.patreon.com/philosophywithoutborders) or purchase his recently published book, The Fate of Analysis (2021).

The Fate of Analysis (2021)

Robert Hanna’s twelfth book, The Fate of Analysis, is a comprehensive revisionist study of Analytic philosophy from the early 1880s to the present, with special attention paid to Wittgenstein’s work and the parallels and overlaps between the Analytic and Phenomenological traditions.

By means of a synoptic overview of European and Anglo-American philosophy since the 1880s—including accessible, clear, and critical descriptions of the works and influence of, among others, Gottlob Frege, G.E. Moore, Bertrand Russell, Alexius Meinong, Franz Brentano, Edmund Husserl, The Vienna Circle, W.V.O. Quine, Saul Kripke, Wilfrid Sellars, John McDowell, and Robert Brandom, and, particularly, Ludwig Wittgenstein—The Fate of Analysis critically examines and evaluates modern philosophy over the last 140 years.

In addition to its critical analyses of the Analytic tradition and of professional academic philosophy more generally, The Fate of Analysis also presents a thought-provoking, forward-looking, and positive picture of the philosophy of the future from a radical Kantian point of view.