Addicted to Crude

Here in Carmerica, nothing is free — not the food, not the fuel, not the people, not me.

Here in Carmerica, deep in the gears of a four-stroke engine lubricated with tears —

You can hear it a-comin’, long before it appears here in Carmerica, deep in the gears.

Here in Carmerica, moments away — the pressure is building just a little each day,

Ready to rumble, let happen what may, here in Carmerica, moments away.

Here in Carmerica, land of the cruel, addicted to sex, and addicted to fuel.

But some of your people are nobody’s fool here in Carmerica, land of the cruel.

Here in Carmerica, divided they stand: They wait undecided, their heads in the sand.

Their confidence wavers, then leaves their command, here in Carmerica, divided they stand.

Here in Carmerica, land that I love: the grind of your dollar, the fist in the glove,

The smooth-runnin’ engine when push comes to shove, here in Carmerica, land that I love.

— Nathan Rogers, Carmerica (yes, he’s Stan’s son, and Canadian)

Our local Facebook page has recently exploded with horrified and outraged revelations that most of the gas stations in our community are closed, because they, like some other specialized retailers these days, have nothing to sell. The signs that recently said $2.39/litre now read $0.00. The underlying message of these social media posts: Who’s to blame for this? and When will this inconvenience be over? If I were to read comments on the posts (which I never do) I’m sure answers to these unanswerable questions would be readily proffered.

We still don’t seem to fathom the idea that complex problems — predicaments really — have no solutions, only stopgaps and workarounds, or that system collapse, which is more in evidence now than ever before, is a gradually unfolding phenomenon, not a sudden Mad Max one-time Hollywood cataclysmic event.

We are living in the early years of what Jim Kunstler tagged “The Long Emergency”, a state of emergency that will last decades and will not be ‘fixed’, but rather will end only when we have learned to adapt to a completely different way and scale of living.

As Nathan’s song tells us, we’re addicted to our current way of life, and to the ruinously destructive systems, most notably fossil fuel extraction, that make that life possible. As Indrajit Samarajiva says, especially in the Global South, we’re going into fossil fuel withdrawal. And there are no drugs on offer to ease the ghastly symptoms.

What exactly does it mean to be addicted to something? It means we can’t function competently without it. It means we react in irrational, unpredictable, and unhealthy ways when we don’t get it. It means we may resort to violence or crime to get it. It means even though we know what we crave isn’t good for us, we will use any means of rationalizing why it would be worse for us to quit using it. It means we’ll deny we have a problem. It means we’ll favor the certain short-term pleasure over the uncertain long-term suffering that quitting would entail. It means we’ll befriend (and vote for) people who will tell us our addiction is OK. And it means the addicts who are poor will suffer disproportionally more than those who are rich.

Beating this addiction isn’t just a matter of collective willpower. There’s a danger that if we convince ourselves that we’re doing our share, or more than our share, we will shrug off facing the fact that most people will never be able to do that. Being personally right won’t provide any solace when it all comes apart, and it may lull us into complacency in the meantime.

We have become addicted to petrochemical products to the same extent and in the same way we are addicted to food, water, and air. Our civilization simply can no longer operate without them. This dependence is not like our dependence on caffeine or alcohol. Breaking that dependence is possible. Breaking our dependence on petrochemicals is not. Everything that supports our civilization depends on it — transportation, heating, cooling and much of our electricity, the fertilizers and other chemicals that are essential inputs to 60% of the world’s current food supply, industrial production, infrastructure, our beloved internet, and substantially every aspect of our present economy. Without it we will simply die, in large numbers. The only way we can significantly reduce this inevitable suffering and death is by having fewer or no children, and it is not clear that many of us are even willing to do this, though that will certainly shift as the horrors of civilizational collapse begin to unfold more fully.

The growth of our industry, our productive capacity, our infrastructure, our food supply, our trade, and our human population — as Richard Heinberg has repeatedly explained, all of these have occurred in lock-step with the growth of our consumption of fossil fuels. That’s because our exploding consumption of fossil fuels is what has entirely powered and enabled that growth, and has been and continues to be entirely dependent on its impossible continuation. It is a myth that, with collective will and effort, we could replace fossil fuels with other energy sources (including sources yet to be invented) without our economy collapsing in the process. And it is a myth that such substitution could prevent or even significantly lessen or mitigate climate collapse and other aspects of the ongoing global ecological collapse fuelling the sixth great extinction of life on the planet.

So to answer my neighbors’ questions:

Who is to blame for these disruptions to our fuel-injected economy and its supply chains? No one. This is what happens when 7.9B people all do their best to look after themselves and the people they care about. Get used to it. Many more disruptions are coming, and some of them are going to make the ones we are now seeing look like a walk in the park.

When’s it going to end, and get properly fixed so it doesn’t happen again? Never. This is a system in terminal collapse. Like all civilizations before us, and their complex systems, this one too will end in chaos, except this time it will be global, with no frontiers left and no replays available. This civilization has used up all of its lives. What will be left of human societies when this civilization’s collapse reaches its conclusion decades from now, we cannot know, though it almost surely will be low-tech, utterly local, and include a lot fewer people than are alive today. There’s a serious chance no humans at all will survive it, though our demise may be a long thin tail that hangs on with a few remaining societies in decline for centuries. The Roman philosopher Seneca wrote of societies: “Fortune is of sluggish growth, but ruin is rapid.” Energy researcher Ugo Bardi has coined this observation the Seneca Cliff, and it is increasingly likely that the collapse curve we are now starting to slide down will be such a cliff.

When our addiction to hydrocarbons can no longer be fed, it will be no different from suddenly finding ourselves without food, without water, or without air. We can go on believing that when the last of the pushers of the drug we crave have all put yellow tape around the pumps and permanently changed their price signs to $0.00, there will be another candy man opening up around the corner to fill the insatiable need. But that belief won’t serve us well when the withdrawal symptoms kick in. We’ll recognize the symptoms: the feeling of being desperately hot, or desperately cold, or desperately hungry, or desperately thirsty, or unable to breathe, or unable to function, or homeless and bankrupt and feeling hopeless and ashamed, or ready to kill for relief, or wanting to die just to end the pain. Not pretty, but some of us will likely survive, and learn to live without what we thought we would always have.

You can hear it a-comin’ long before it appears.+

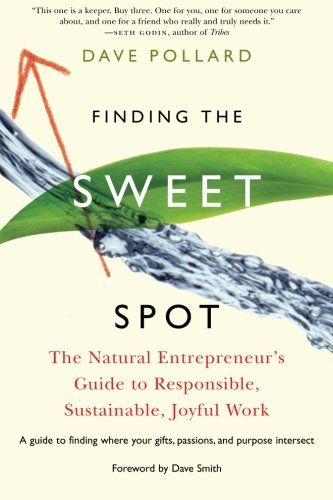

Finding the Sweet Spot: the natural entrepreneur's guide to responsible, sustainable, joyful work

"Now what am I going to do?" is a question many people ask—and leave unanswered—at critical potential turning points in their careers. Perhaps you’re a new graduate, but instead of lining up for a boring entry-level job at a big corporation, you wish you could start your own sustainable and responsible business